Agent57: Outperforming the human Atari benchmark

Highlights

- Agent57 is able to perform well on all 57 Atari games in the Atari Learning Environment (ALE)1

- Q-function is split in two to decompose the contribution of intrinsic and extrinsic rewards

- A meta-controller modeled as a bandit problem controls the tradeoff between exploration and exploitation

Introduction

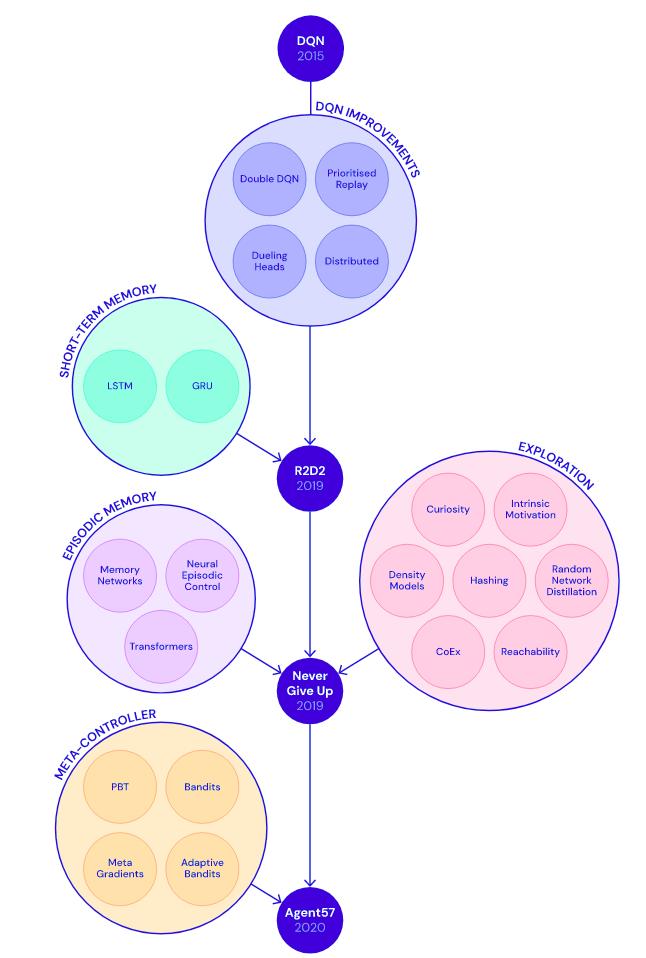

A condensed history of improvements that led to Agent57

source: Deepmind blog

Never Give Up (NGU)2 was a monumental success as it was the first agent to achieve good performance on hard-exploration games. However, it conversely failed to gain good scores on “easier” games. The authors hypothesize that this is because, at each episode, NGU uniformly assign a family of more explorative or exploitative agents at random to gather episodes. This process, according to the authors, is suboptimal as the need for exploration or exploitation varies when learning a game as well as with different games.

Methods

State-action value function parameterization

The authors propose to split the state-action value function (Q) into this:

\[Q(x, a, j; \theta) = Q(x,a,j;\theta^e) + \beta_j Q(x,a,h;\theta^i)\]where \(j\) is a one-hot vector pointing to the \((\beta, \gamma)\) pair controlling exploration and discount for the actor, just like in NGU. The authors show in the appendix that this decomposition is valid and that the optimization of this Q-function is equivalent to the optimization of a single Q-function with reward \(r^e + \beta_j r^i\).

Adaptive Exploration over a Family of Policies

NGU uses a family of explorative and exploitative policies during training and trains them all equally, regardless of their actual contributions to the learning process. The authors propose using a meta-controller to select which policies will be used at training and testing time. To do so, the authors propose posing the policy selection as a non-stationary multi-arm bandit problem. At the beginning of each episode, the meta controller selects a bandit “arm” to assign a pair \((\beta, \gamma)\) per actor. One can imagine that policies with a higher \(\beta\) and a lower \(\gamma\) might be better suited at the beginning of training while the opposte will be true in the later on.At test time, the controller will select which policy is better suited, with arms having a wide range of \(\gamma\) and \(\beta \approx 0\). This allows for far less fine-tuning per-task as the meta-controller decides for itself which policy should be used.

Because the needs for exploration and exploitation change over time, the bandit problem is considered non-stationary. This means that an algorithm like Upper-Confidence Bound (UCB)3 would not work. To alleviate the problem, the authors employ a “sliding-window” UCB, which is described in the appendix.

Data

The agent was trained separately on all 57 games in the ALE1 using only a using a single set of hyperparameters

Results

Conclusions

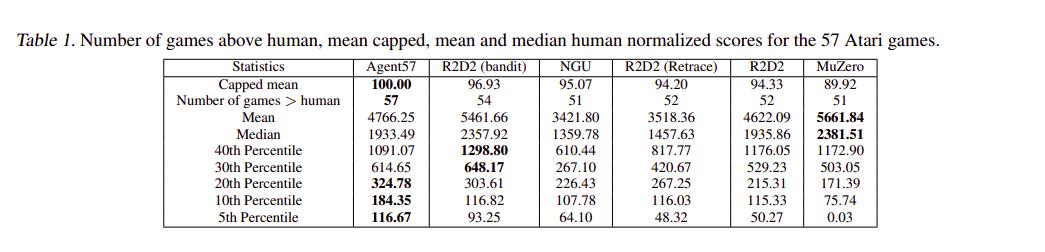

While MuZero still obtains better mean and median performance, Agent57 is able to get above human-level performance on all 57 games and is the first to do so.

Remarks

- Although it makes sense to do so, the motivations and results of splitting the state-action value function are hidden in the appendix H.6 and a website showing the improvements, here.

- It is interesting to see a SotA paper using multi-armed bandits

- Agent57 builds on a looooong line of improvements to DQN

- A lot of information was relayed to the appendix

References

-

NGU: https://vitalab.github.io/article/2020/05/28/NGU.html ↩

-

UCB and sliding-window UCB: https://arxiv.org/pdf/0805.3415.pdf ↩