DreamerV3: Mastering Diverse Domains through World Models

Highlights

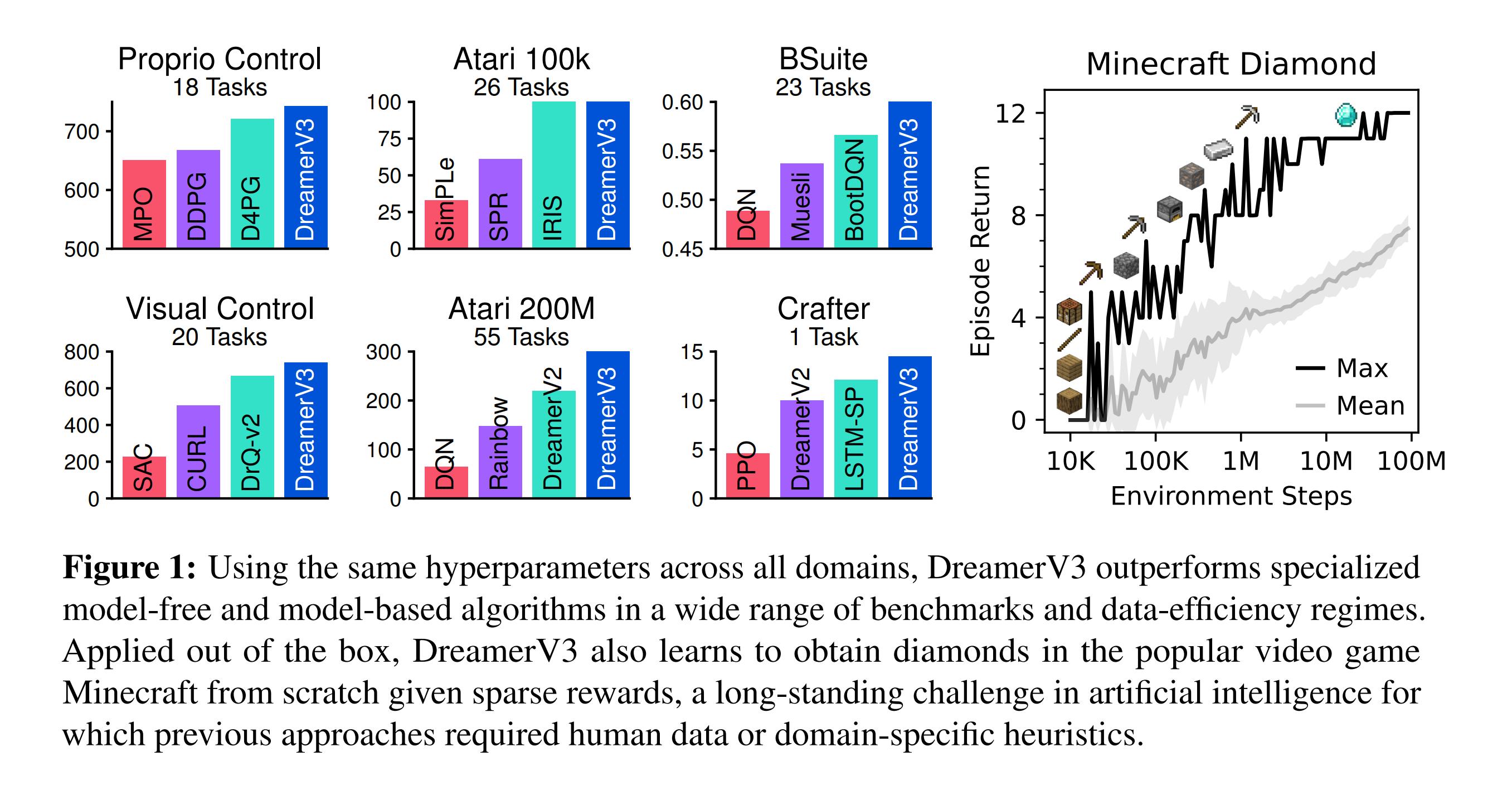

- Single algorithm and set of hyperparameters achieves high performance on a large variety of environments

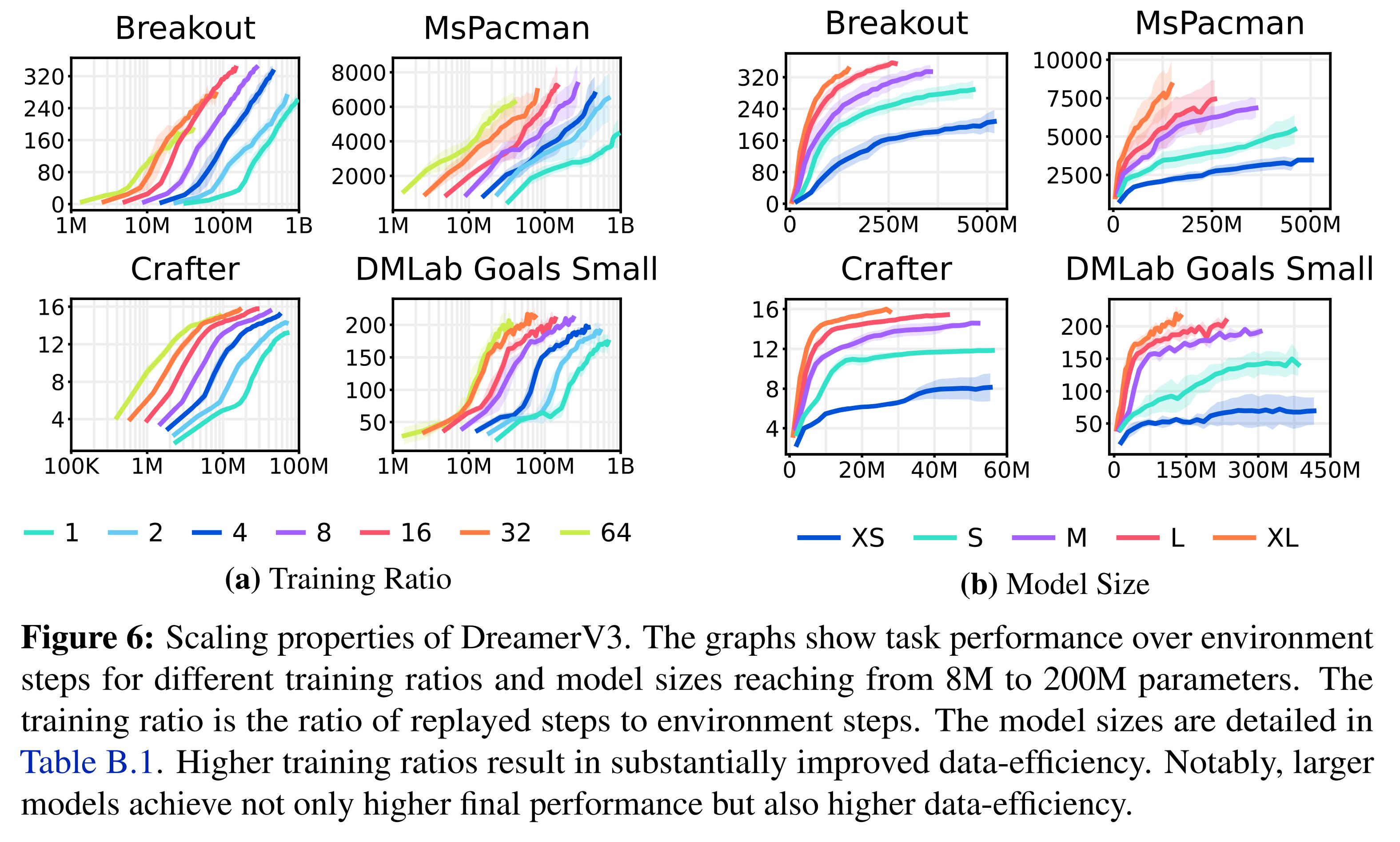

- More parameters and more replay lead to better data efficiency

Introduction

Reinforcement learning (RL) can be applied to problems that are wildly different to each other, with continuous or discrete actions, high or low dimensional states, dense or spare rewards, etc. Applying an existing algorithm to a new problem often involves extensive fine tuning to find a good set of hyperparameters. Moreover, the learning process is often very brittle, which prohibits the use of large models.

Model-based reinforcement learning is a type of RL where the agent will not only learn a policy, but also a world model which the agent can use to plan ahead. DreamerV3 builds upon DreamerV21, but does not significantly change the algorithm. Instead, a “bag of tricks” is employed to stabilize and normalize learning across a wide range of environments.

Methods

Architectures and losses

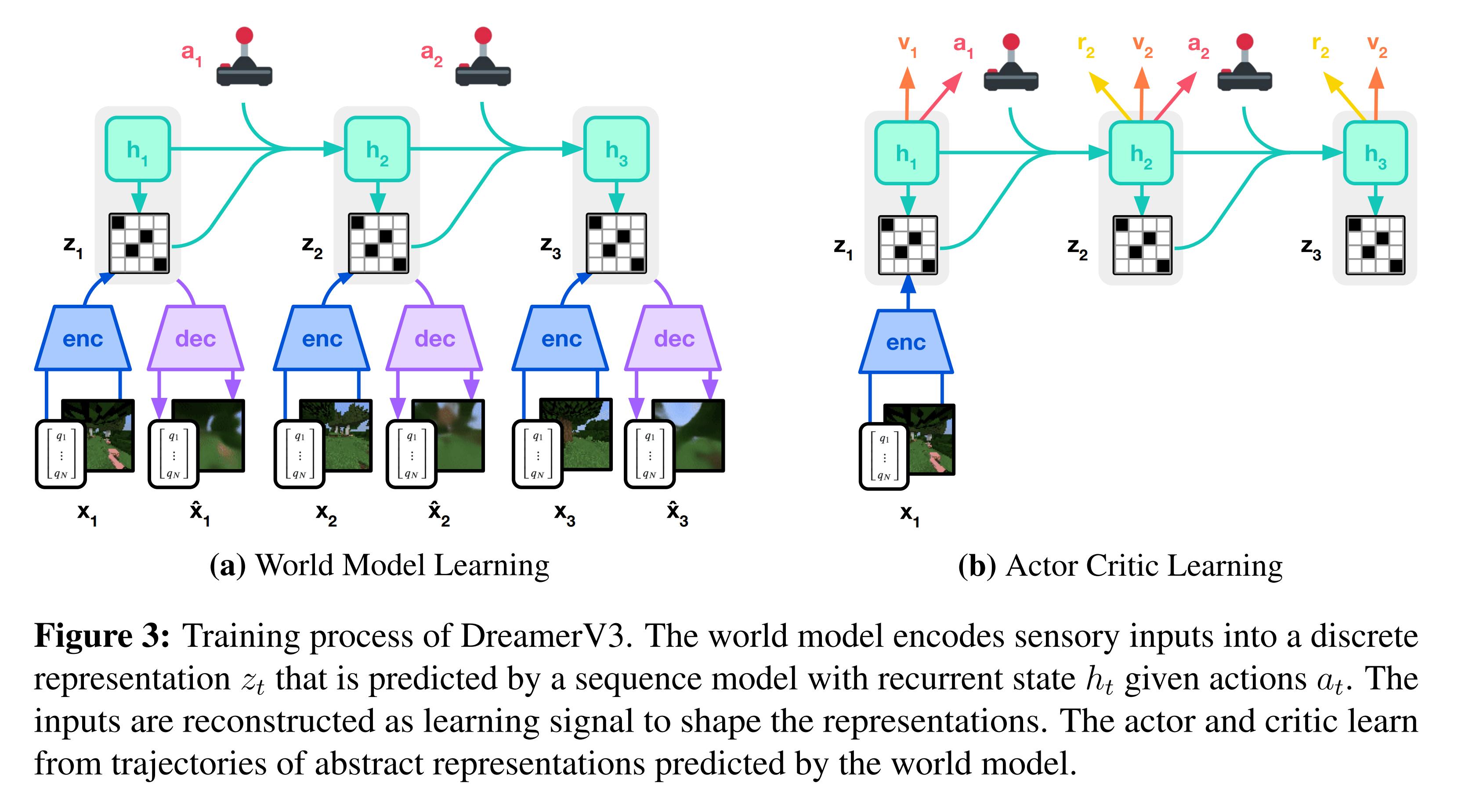

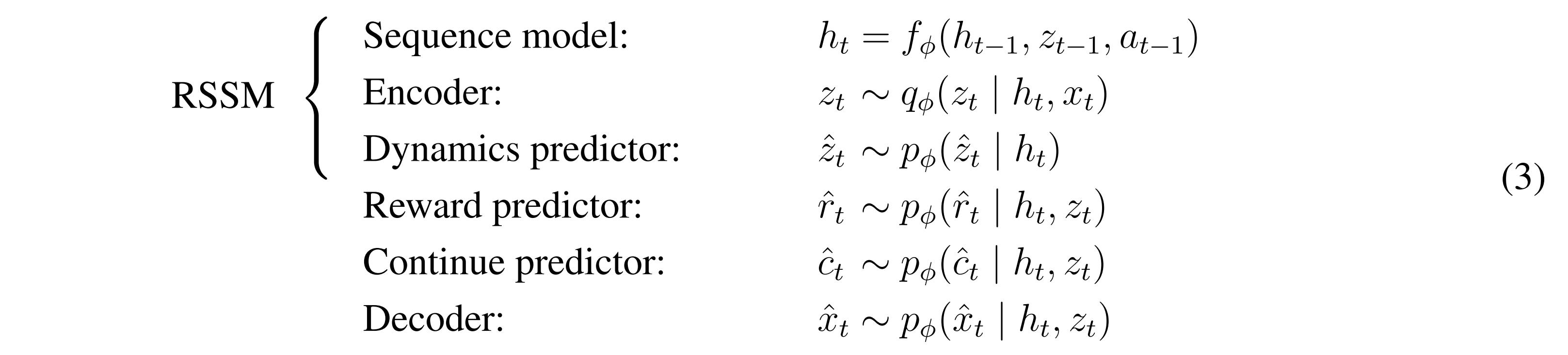

The DreamerV3 architecture is essentially the same as in DreamerV2 and is pictured in the figure above. The world model, dubbed the “Recurrent State-Space Model (RSSM)” can be described by the following networks:

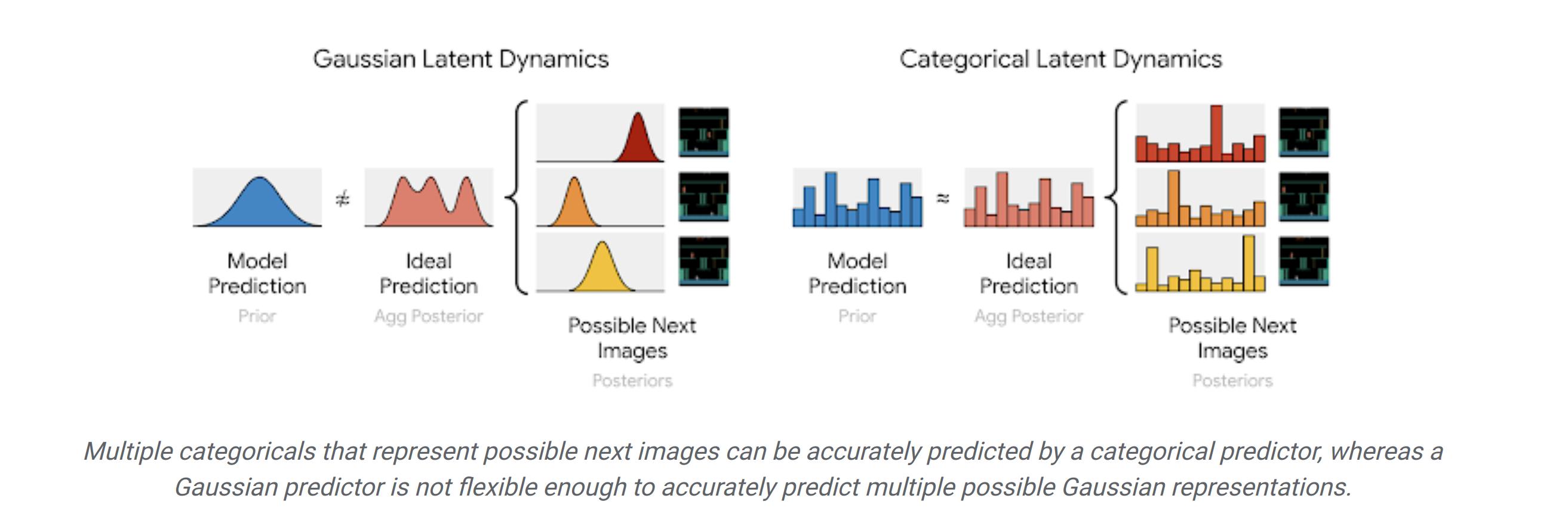

Note that the encoder and the dynamics predictor both predict \(z_t\), but the dynamics predictor does so with only \(h_t\). The latent representation of the space \(z_t\) is a set of 32 one-hot vectors sampled from 32 categorical distributions output by the encoder \(q_\phi\) and the dynamics predictor \(p_\phi\). The authors argue that the categorical distributions provide more expressivity than using gaussian distributions, for example.

https://ai.googleblog.com/2021/02/mastering-atari-with-discrete-world.html

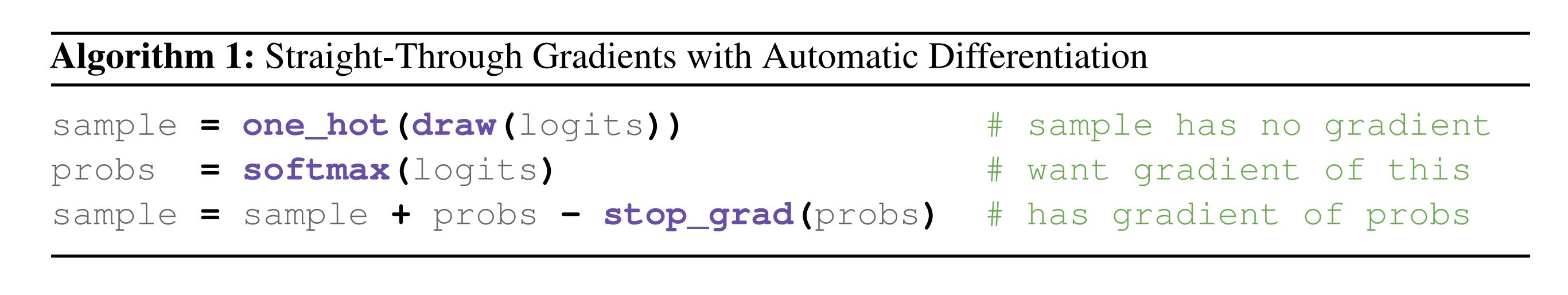

To sample the categorical distributions as one-hots and be able to backpropagate though them, the authors use “straight-through gradients”2:

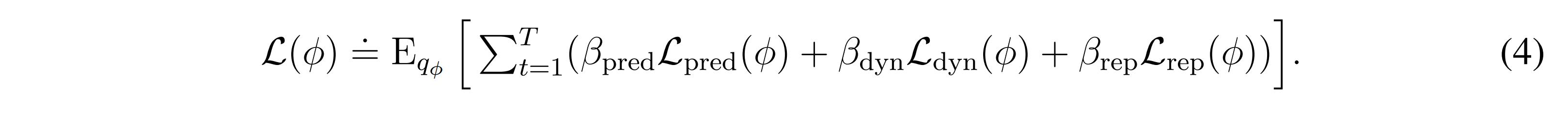

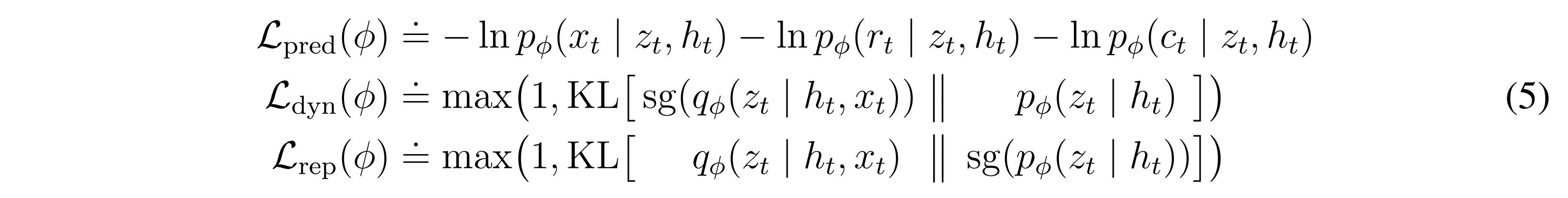

The RSSM is trained via a set of three losses:

\(\mathcal{L}_{dyn}\) and \(\mathcal{L}_{rep}\) make sure that the two representations match and are not trivial through a process called KL balancing.

The Actor-Critic is trained to propose actions and estimate their return solely on a the latent space predicted by the dynamics predictor. This way, only a single input state is needed to evaluate actions in the future. The actor is trained using REINFORCE and the critic is trained using \(\lambda\)-returns.

To train the model, the environment is explored for some steps, which are then used to train the world-model, then the actor-critic. Then, the environment is explored some more and the process repeats. The total number of steps perfomed depends on the environment. The gradients of the actor-critic do not backpropagate through the world model.

Tricks

While the architecture of DreamerV2-3 is somewhat straightforward, several tricks are employed to make the training robust to the wide variety of environments.

Symlog

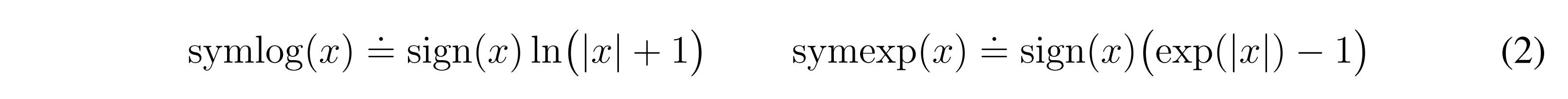

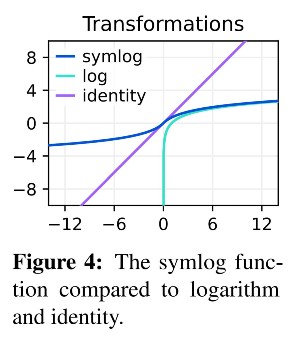

Different environments may produce different reward distributions. Some may output very large and sparse rewards, others small by very dense rewards. As such, there needs to be some form of normalization to provide the agent with a similar loss amplitude across all environments. To do so, the authors introduce the symlog function (and its inverse, symexp):

The symlog function squashes large positive and negative values while preserving small values. The symlog function is used “in the decoder, the reward predictor, and the critic. It also squashes inputs to the encoder[sic]”.

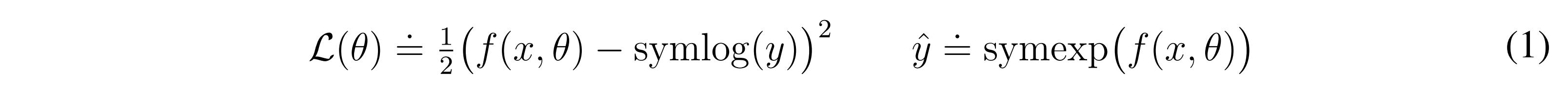

While there is no explicit mention as to why this is done, the symlog function is not applied directly. Instead, a network is trained to predict the symlog function such that

Free bits

Readers with a keen eye may have spotted that the KL-balancing terms are clipped below 1 nat. The authors argue this is to “avoid a degenerate solution where the dynamics are trivial to predict but contain not enough information about the inputs. […] This disables them while they are already minimized well to focus the world model on its prediction loss”.

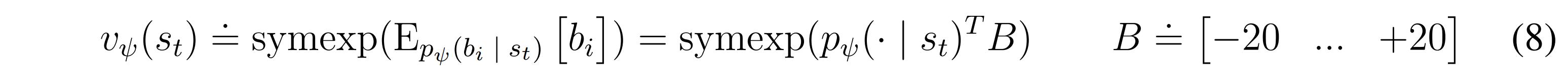

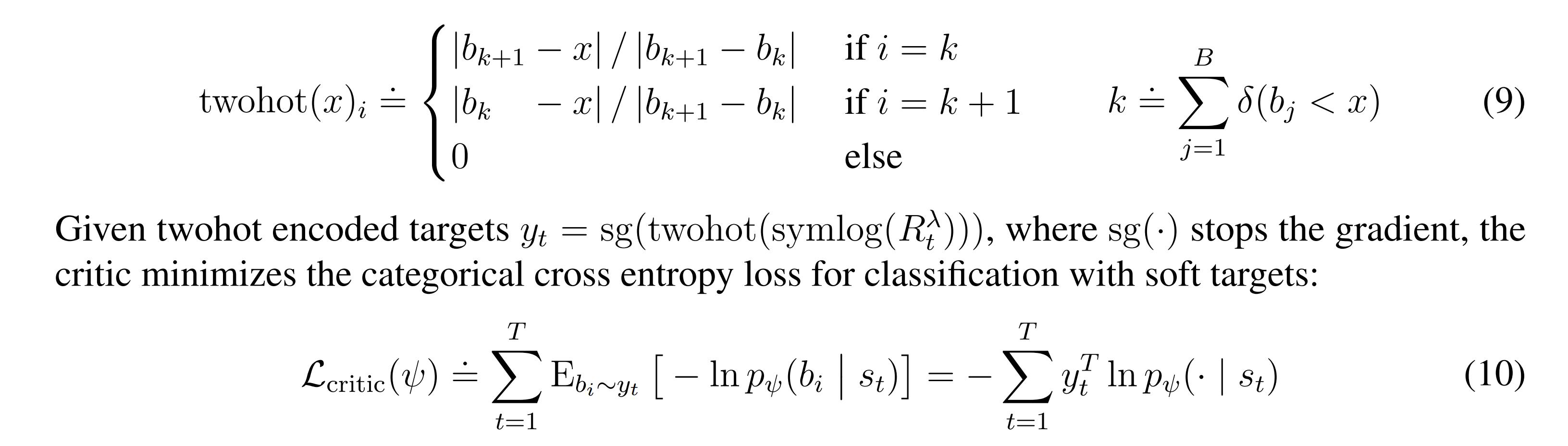

Two-hot reward encoding

In environments with a widespread distribution of returns, predicting the expected returns by the critic might not be descriptive enough to train the actor. Instead, the rewards are transformed into two-hot encoding such that:

Other tricks are employed but I did not think they were worth mentioning.

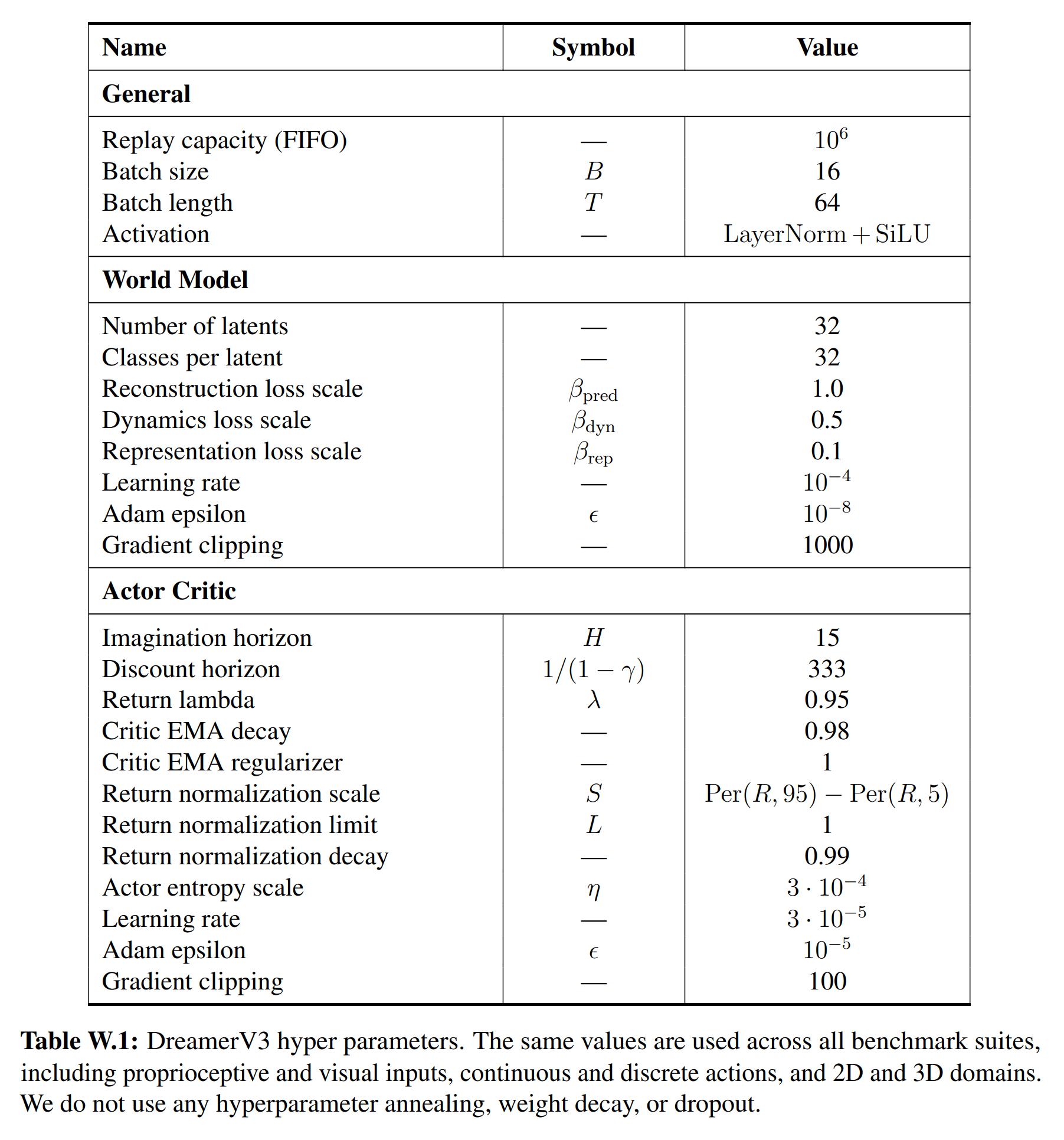

Below is a list of the hyperparameters used across all tasks:

Environments

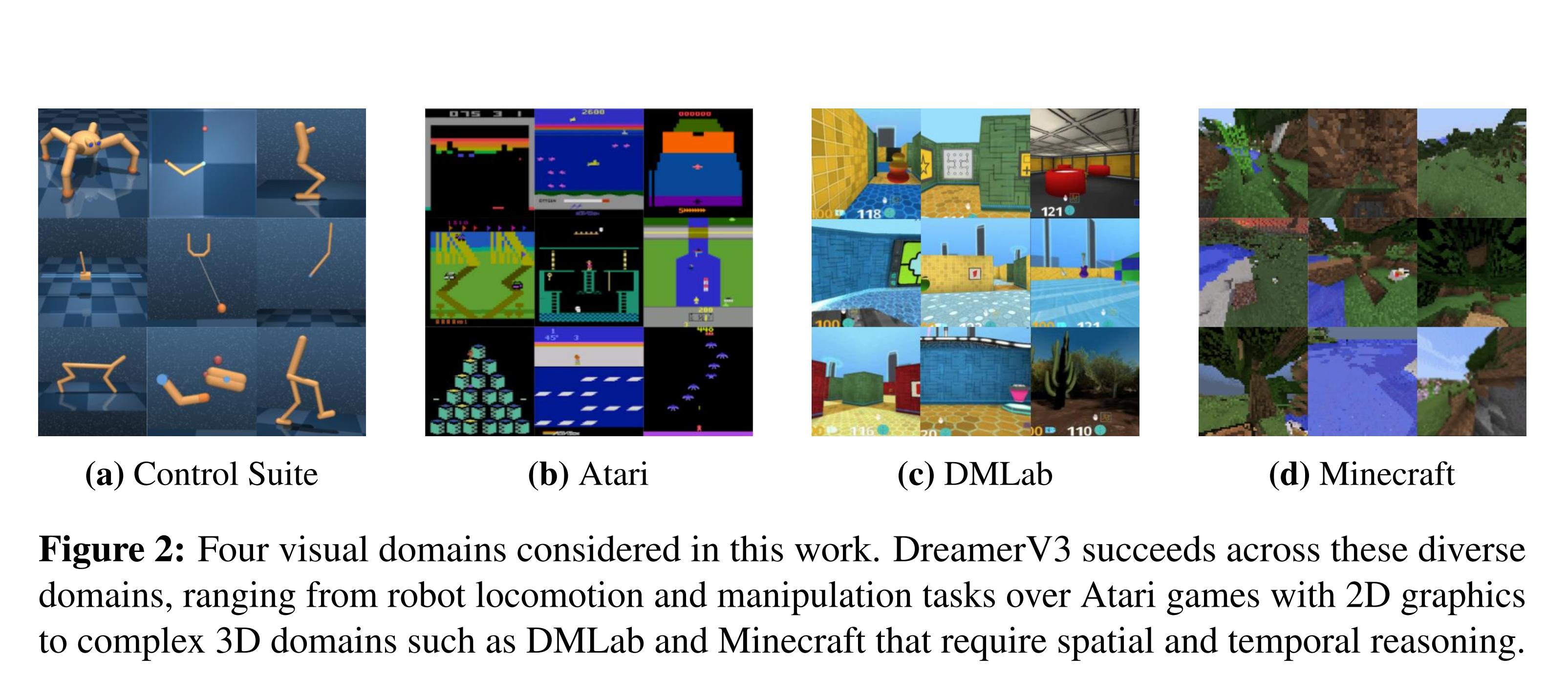

- Proprio Control Suite: a robotic control suite (think Mujoco) with low-dimensional input (joints configurations)

- Visual Control Suite: the same robotic control suite, but the agent receives a high-dimensional input (camera images)

- Atari 100k: 26 Atari games where the agent is limited to 100k steps, equating around 2 hours of play.

- Atari 200M: 55 Atari games where the agent is limited to 200M steps.

- BSuite: “This benchmark includes 23 environments with a total of 468 configurations that are designed to test credit assignment, robustness to reward scale and stochasticity, memory, generalization, and exploration”

- Crafter: A sort of 2D Minecraft

- DMLab: A 3D, first-person environment where exploration and long-term goal planning is necessary.

- Minecraft: A modified version of the popular video-game Minecraft. Sparse rewards are given to the agent when it accomplishes certain goals like crafting tools and collecting specific resources.

Results

Full results are available in the appendices of the paper. Generally, the agent outperforms specialized algorithms with a single set of hyperparameters.

The authors also investigate the scaling properties of their algorithm, leading to very positive results.

Remarks

- The results are certainly impressive, considering that the model was trained on a single V100 GPU

- The current version on arXiv is a complete mess to read and presumes the reader is very familiar with previous versions of Dreamer (DreamerV2, DreamverV1 and PlaNET).

Footnotes

-

Hafner, D., Lillicrap, T., Norouzi, M., & Ba, J. (2020). Mastering atari with discrete world models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.02193. ↩

-

Bengio, Y., Léonard, N., & Courville, A. (2013). Estimating or propagating gradients through stochastic neurons for conditional computation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1308.3432. ↩