What Matters in Learning from Offline Human Demonstrations for Robot Manipulation

In this post I examine the content of the article from a reinforcement learning-centric point of view, but the article is focused on learning from a fixed set of demonstration in general, either via imitation learning or reinforcement learning.)

Highlights

- Current offline reinforcement learning (RL) datasets were conceived from RL agents transitions

- Learning from human demonstrations does not work with current state-of-the-art offline RL algorithms

- Temporality (i.e. recurrent or future-predicting models) helps when learning from human datasets

Introduction

Offline RL is a type of RL where transitions are not gathered by the learning agent, but instead provided by a fixed dataset. Recent advances in offline RL have shown incredibly promising results leveraging often suboptimal data to learn optimal policies.

Offline RL datasets such as D4RL1 are often gathered from the learning process of RL agents. However, some tasks (such as robotic manipulation) are yet to be solved by online RL. Datasets gathered from human demonstrations are therefore an appealing alternative.

In this work, the authors state five challenges of learning from human demonstrations. From the blog post2:

-

(C1) Humans are non-markovian: humans act on more factors than just the information they have in front of them at each time, such as their memory, their prior experience, etc.

-

(C2) Varying trajectory quality: different humans have different control skills for the task at hand

-

(C3) Dataset size: learning agents have to have sufficient coverage in the dataset to be able to handle all the situations they might encounter

-

(C4) Discrepancies in objectives: Agents are trained to replicate the behavior in the dataset, but this is a different objective from the underlying objective: be successful at the task at hand.

-

(C5) Design decisions: Hyperparameters can have a heavy impact of the agent’s performance.

Methods

Data

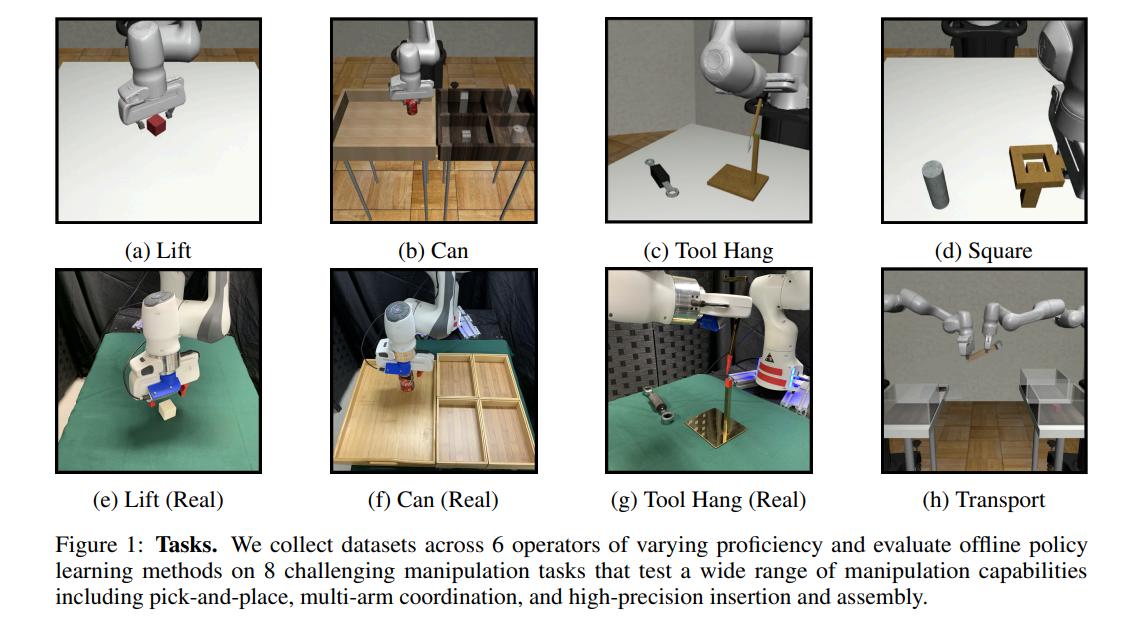

To explore the above challenge, the authors devised 8 robotic manipulation tasks:

- Lift (sim + real)). The robot arm must lift a small cube. This is the simplest task.

- Can (sim + real). The robot must place a coke can from a large bin into a smaller target bin. Slightly more challenging than Lift, since picking the can is harder than picking the cube, and the can must also be placed into the bin.

- Square (sim). The robot must pick a square nut and place it on a rod. Substantially more difficult than Lift and Pick Place Can due to the precision needed to pick up the nut and insert it on the rod.

- Transport (sim). Two robot arms must transfer a hammer from a closed container on a shelf to a target bin on another shelf. One robot arm must retrieve the hammer from the container, while the other arm must clear the target bin by moving a piece of trash to the nearby receptacle. Finally, one arm must hand the hammer over to the other, which must place the hammer in the target bin.

- Tool Hang (sim + real). A robot arm must assemble a frame consisting of a base piece and hook piece by inserting the hook into the base, and hang a wrench on the hook. This is the most difficult task due to the multiple stages that each require precise, and dexterous, rotation-heavy movements.

From these tasks, the authors gathered (at most) three datasets for each:

- Machine-Generated (MG). Transitions obtained during the training process of an RL (SAC) agent. Only datasets for the Lift and Can tasks were gathered as they could not successfully train an online RL agent on the others.

- Proficient-Human (PH). Transitions obtained from a single experienced human operator.

- Multi-Human (MH). Transitions obtained from a group of six human operators with varying skill levels.

Each dataset has both low-dimension observations and images from cameras.

Algorithms

The authors considered six algorithms for the tasks:

- BC*: Behavior cloning (L2 loss on the action or KL divergence between the behavior policy and the learning policy (noted as Gaussian Mixture Models, GMM))

- BC-RNN*: Behavior cloning but with a recurrent policy

- HBC: Hierarchical Behavioral Cloning, which includes two policies, a high-level one (with predicts future states) and low-level one (with predicts actions).

- BCQ: Batch-Constrained Q-Learning, an offline RL algorithm.

- CQL: Conservative Q-Learning, an offline RL algorithm.

- IRIS: Implicit Reinforcement without Interaction, an offline RL algorithm. Also hierarchical, IRIS uses a RNN for its low-level policy.

* not actually reinforcement learning.

Experiments

The authors devise 7 experiments to test the challenges proposed above:

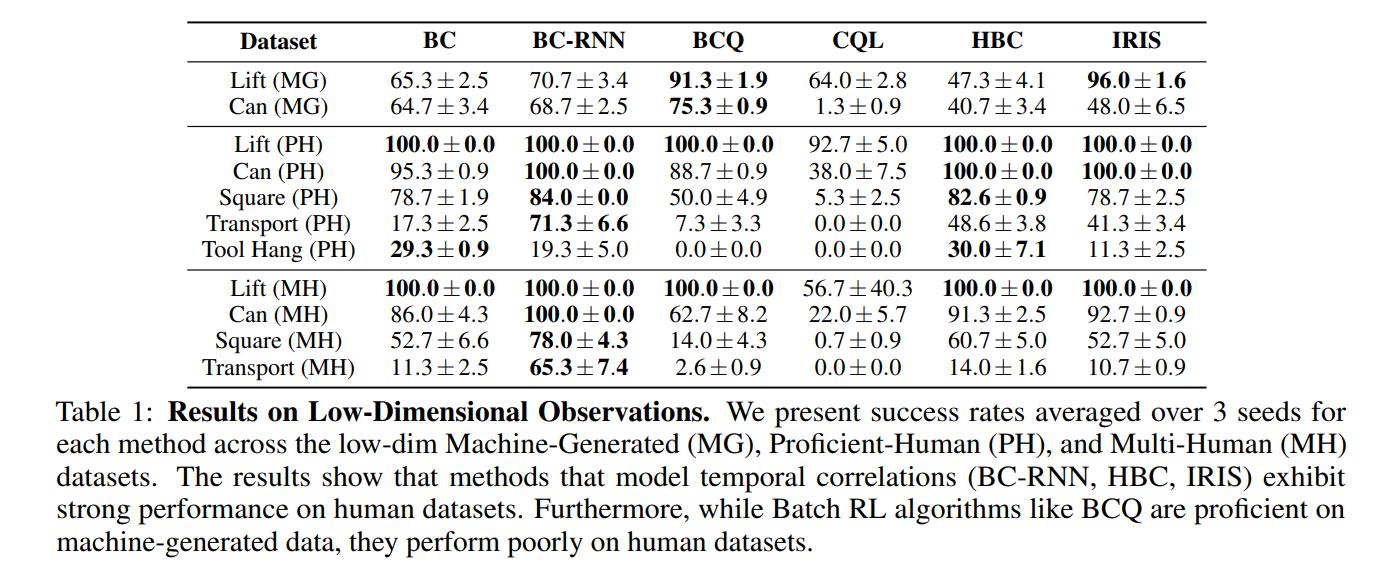

- Algorithm Comparison (C1, C2): the authors test all the algorithms on all the datasets and tasks using low-dimension representations as states.

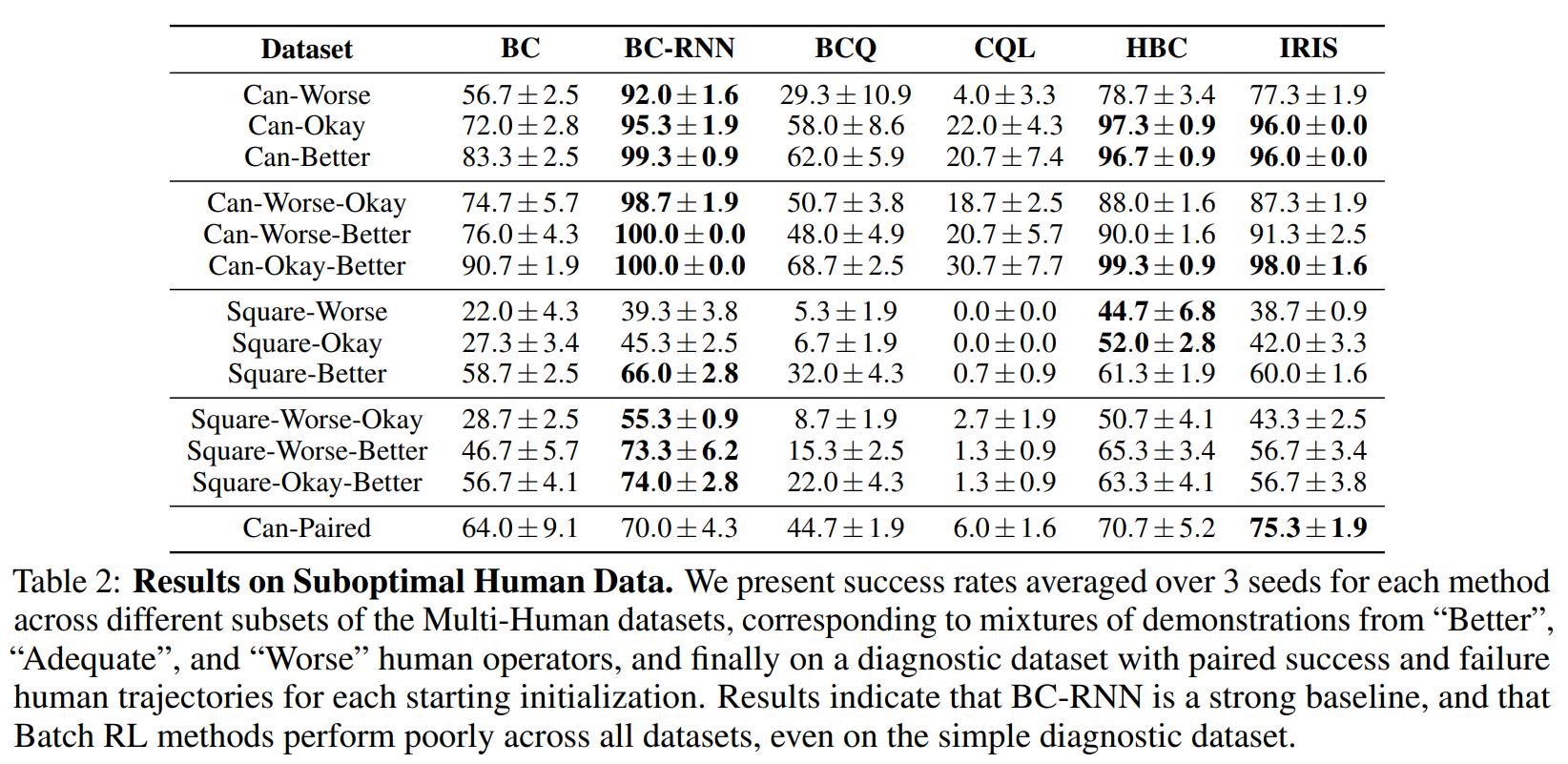

- Learning from Suboptimal Human Data (C2): the authors split the MH dataset into varying quality sub-datasets and train on them to see the effect of the trajectory quality

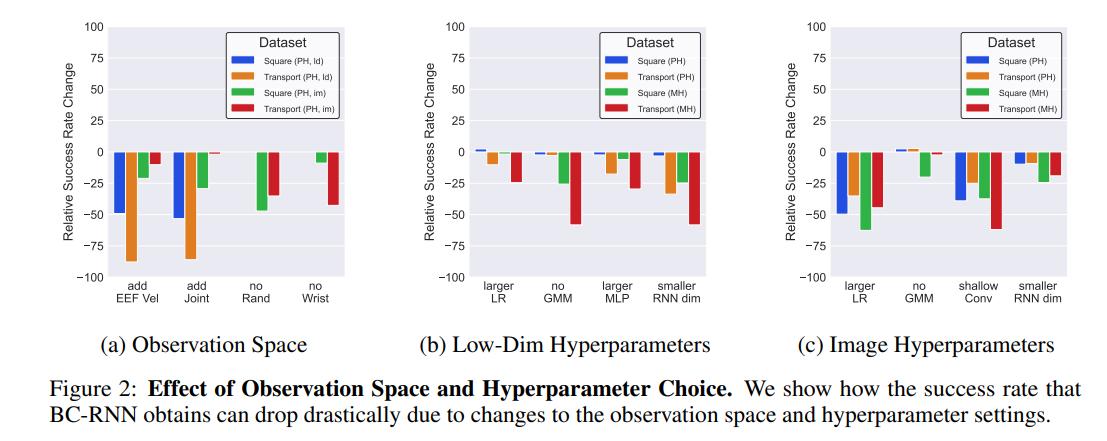

- Effect of Observation Space (C5): The authors evaluate the discrepancies in performance between learning from images or low-level features

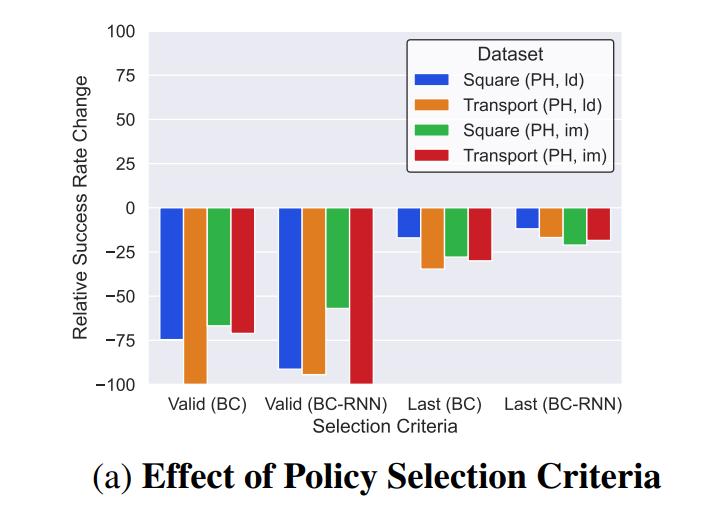

- Selecting a Policy to Evaluate (C4): the authors evaluate the drops in performance when either selecting agents with the lowest validation loss or at the last checkpoint, instead of selecting them via online evaluation.

- Effect of Hyperparameter Choice (C5): The authors vary hyperparameters for the BC-RNN agent

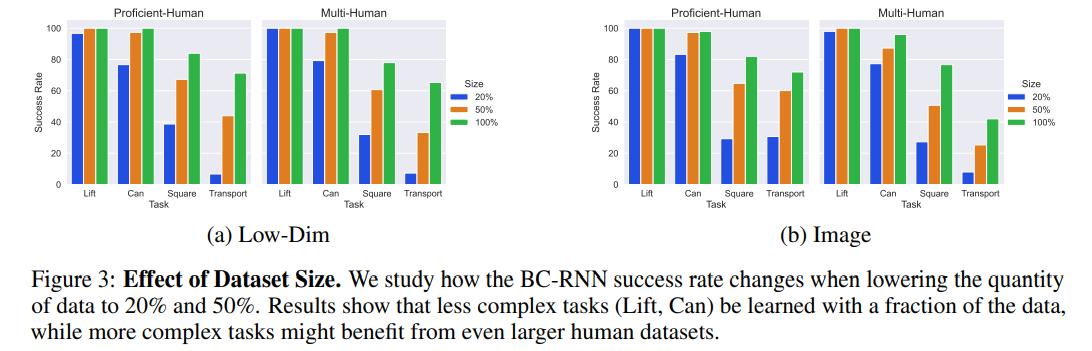

- Effect of Dataset Size (C3): the authors vary the percentage of data used

- Applicability to Real-World Settings: the authors train on the real version of three tasks using hyperparameters found for the simulated versions.

Results

Exp. 1

1.1 BC-RNN performs much better than BC

1.2 Offline RL does not work on human data

Exp. 2

Can-Paired is a balanced dataset where a single human operator purposely succeeded and failed 100 times each at the task.

2.1 BC-RNN outperforms other algorithms except IRIS and HBC, which both also have some notion of temporality.

2.2 CQL failed even in the Can-Paired test, where it should have been the best at distinguishing good from bad transitions.

Exp. 3

3.1 Agents trained on images can match agents trained on low-level features

3.2 Adding extra features (like velocities) hurt the performance of agents

3.3 Data augmentation on image inputs and other observations greatly improved results

Exp. 5

3.1 Low-level agents are more tolerant to the LR

3.2 GMM models performed better than deterministic models

3.3 Using a bigger MLP encoder for the RNN reduced performance

3.4 Using a smaller conv encoder instead of the ResNet backbone reduced performance

3.5 Using a smaller RNN reduced performance

Exp. 4

4.1 In both cases, the selected policies were worse than the baseline

Exp. 6

- BC-RNN can still learn a good policy without 100% of the data.

Discussion

The authors provide five lessons to be learned from the experiments.

(L1) Algorithms which include some notion of temporality seem promising for learning from human datasets

(L2) Offline RL algorithms need to improve on learning from suboptimal human datasets

(L3) Policy selection is a hard problem in the offline setting

(L4) Observation space and hyperparameters matter.

(L5) Learning from human data is promising

(L6) Transferring to the real world from simulation can work.

Remarks

- Exp.2 gives kind of strange results, as BC-RNN is able to learn an optimal policy from partly sub-optimal data. However, because it’s only BC and not RL, it shouldn’t distinguish better from worse transitions. The only explanation I can think of is that, in an appendix, we can see that better operators produced shorter episodes (i.e. they took less time to solve the task). I think this may have the effect of making better transitions “simpler” to learn that worse transitions, leading to BC-RNN learning an optimal policy despite being exposed to less-than-optimal data.