AlphaGo/AlphaGoZero/AlphaZero/MuZero: Mastering games using progressively fewer priors

Highlights

- AlphaGo defeated the Go champion Lee Sedol in 2016 in a best-of-five tournament

- Since then, Deepmind has released three subsequent versions of the algorithm, each imposing fewer priors and increasing performance

Introduction

In 2016, Deepmind famously put AlphaGo against Go world-champion Lee Sedol and won four matches out of five in tournament. Surprisingly, the algorithm used both recent advances in supervised machine learning and deep reinforcement learning as well as the classical heuristic search algorithm Monte Carlo tree search.

Monte Carlo Tree Search

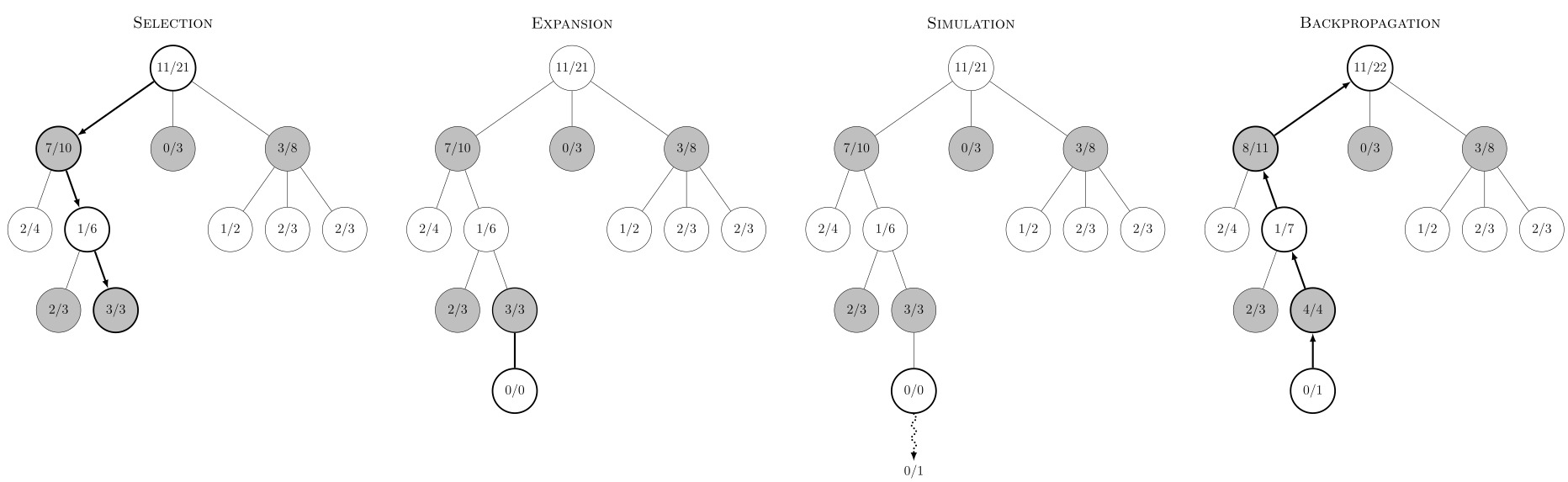

source: wikipedia.org

Monte Carlo tree search (MCTS) was actually first introduced in 2006 to play the game of Go1 and won the 10th computer-Go tournament. It has since then been applied to many problems including chess, shogi, bridge, poker, and video games such as Starcraft.

As the name implies, MCTS is a tree search algorithm that uses Monte Carlo sampling of the search space to iteratively refine the evaluation of nodes. From a root node, child nodes are traversed until a leaf node is reached. A leaf node is a node that has one or more children that has not been evaluated, or a node that has no children because it is a terminal node, or a node that is “deeper” than a maximum depth constraint. Then, a child is selected and a rollout (selecting actions according to a possibly random policy until the end of the game) is performed, assigning the result to the node. Finally, the node’s value is “backpropagated” to parent nodes. Finally, the optimal action can be inferred from the node’s values. This process is repeated for each move.

Several strategies exist to select the next node \(s'\) to explore, but the most popular is to model the children nodes \(s'_{j}\) as independent multi-armed bandits and use the Upper Confidence bound for Trees (UCT) heuristic defined as

\[s' = \argmax_{s'_{j}} = X_j + 2C \sqrt{\frac{2\ln n}{n_j}}\]where \(X_j\) is the value of the node, \(C > 0\) is an exploration factor, \(n\) is the number of times the parent has been visited, and \(n_j\) the number of times the child has been visited. Division by zero is resolved to infinity, forcing the exploration towards yet-unexplored children nodes.

Algorithms

AlphaGo

Silver, D., Huang, A., Maddison, C. et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 529, 484–489 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16961

Silver, D., Huang, A., Maddison, C. et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 529, 484–489 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16961

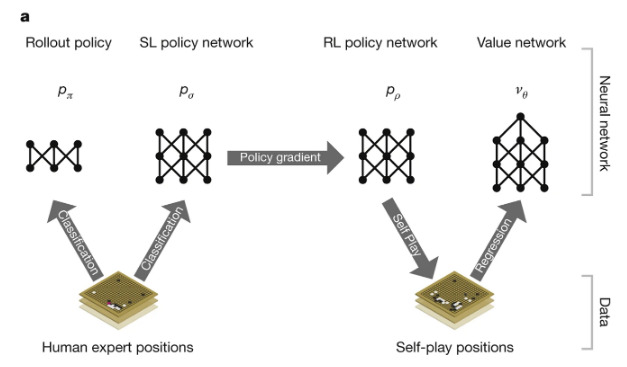

AlphaGo uses several networks to learn to predict the next move to make. First, a small rollout policy \(p_\pi\) and a bigger policy \(p_\sigma\) are trained via supervised learning to predict the winner of the game based on state representations. Even though \(p_\pi\) only achieves ~24% accuracy and \(p_\sigma\) ~57%, they are still useful at later steps. Once both policies are trained, \(p_\sigma\) is used to initialize \(p_\rho\), which is trained via self-play. Frames from \(p_\rho\) are then used to train \(v_\theta\), which learns a value function for states

\[v_\theta (s) = \mathbb{E}[z_t | s_t=s, a_{t...T} \sim p_\rho]\]with \(z\) being the outcome of the game, \(\pm 1\) depending on the player. \(v_\theta\) was trained on a collection of 30 million game states, each from a different game played by versions of \(p_\rho\) so as to provide decorrelated labeled data thus reducing overfitting.

Silver, D., Huang, A., Maddison, C. et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 529, 484–489 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16961

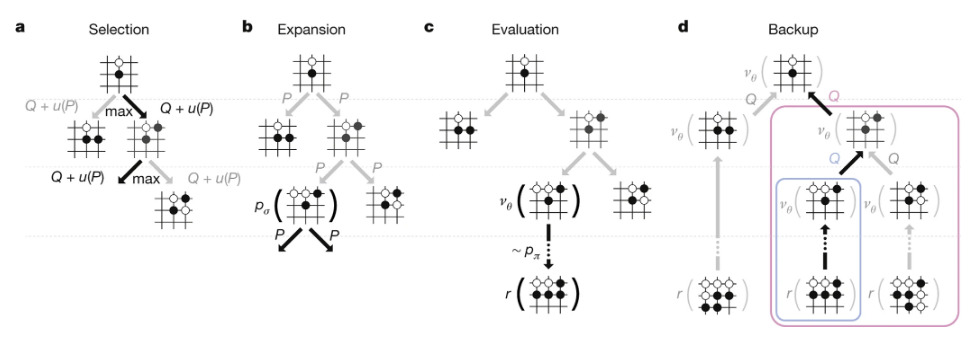

Once training is over, MCTS is used to play the game. At each node, the action \(a\) is selected according to

\[a_t = \argmax_a (Q(s_t,a) + u(s_t,a))\]with

\[u \propto \frac{P(s,a)}{1 + N(s,a)}\] \[P(s,a) = p_\sigma(s,a)\] \[N(s,a) = \sum_{i=1}^N 1(s,a,i)\] \[Q(s,a) = \frac{1}{N(s,a)}\sum_{i=1}^n 1(s,a,i)V(s_L^i)\] \[V(s_L) = (1-\lambda)v_\theta (s_L) + \lambda z_L\]\(p_\pi\) is used during rollouts due to its smaller size and therefore faster inference.

Silver, D., Huang, A., Maddison, C. et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 529, 484–489 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16961

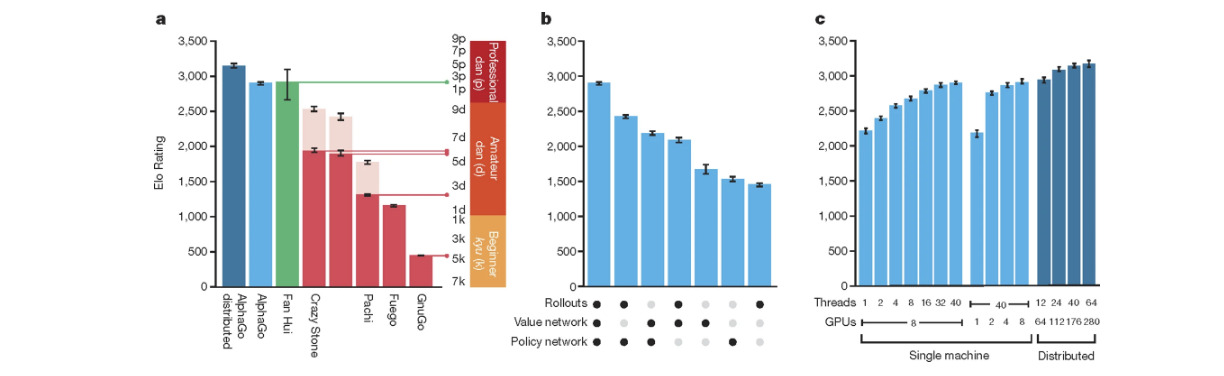

Above is the ELO rating for AlphaGO and European Go champion Fan Hui, as well as other Go programs and different versions of AlphaGo. AlphaGo went on to beat Lee Sedol 4-1 afterward.

AlphaGo Zero

In a subsequent paper, Deepmind presented AlphaGo Zero, which achieves higher performance than AlphaGo using fewer priors.

Silver, D., Schrittwieser, J., Simonyan, K. et al. Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge. Nature 550, 354–359 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24270

A couple of differences are to note:

- No supervised learning is used to initialize policies

- A single policy is used

- A single network is used for both the policy and the value function

- The network is fed raw board configurations instead of handcrafted features

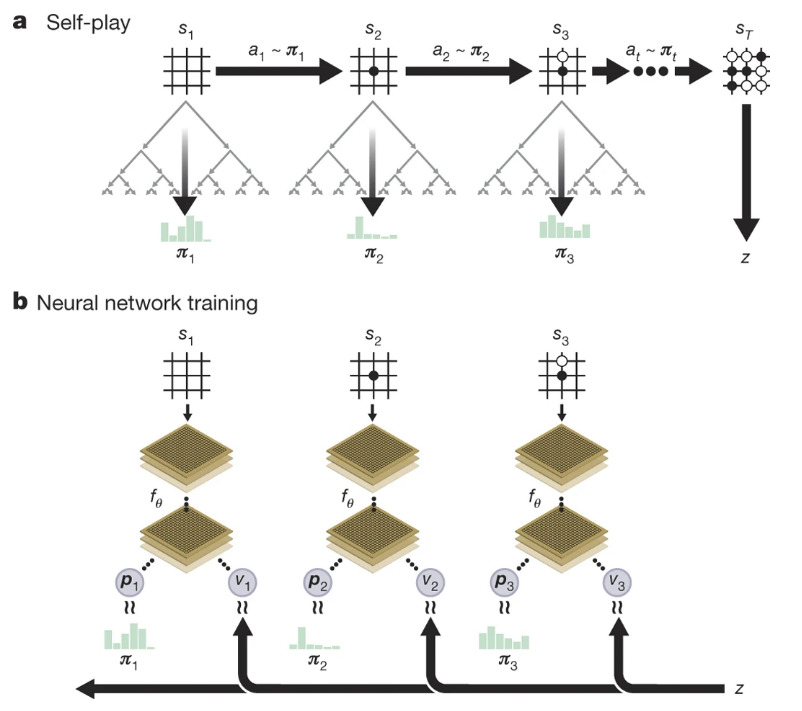

This new version of the algorithm takes the form

\[p, v = f_\theta(s)\], meaning that the network outputs both action probabilities \(p\) and value estimation \(v\) for states \(s\). During training, at each move, the network performs MCTS simulations following

\[a_t = \argmax_a U(s,a)\]with

\[U(s,a) = Q(s,a) + c \cdot p(s,a) \cdot \frac{\sqrt{\sum_b N(s,b)}}{1+N(s,a)}\] \[Q(s,a) = \frac{1}{N(s,a)}\sum_{s'|s,a\rightarrow s'}v(s')\; \text{(an average of the values of the nodes from s' to s)}\]and \(c\) a parameter promoting exploration. However, instead of performing rollouts, the network uses \(v(s_L)\) to predict the outcome. MCTS’ execution gives the tuple \((s, \pi, p, \_)\) where \(s\) is the game’s state, \(\pi\) is a vector that corresponds to the normalized state/actions number of evaluations

\[\pi(s, \cdot) = \frac{N(s, \cdot)^{1/\tau}}{\sum_b N(s,b)^{1/\tau}}\]with \(\tau\) a temperature parameter controlling exploration. \(p\) is the action probabilities for state \(s\), and \(\_\) is later filled with \(z \in \pm 1\) depending on the game’s outcome. Then, the loss function

\[l = (z - v)^2 - \pi^T \log p + c \|\theta\|^2\]is used to train the network with \(c\) in this case being a regularization term. We can interpret the loss as cross-entropy forcing the policy to match MCTS’ behavior.

Silver, D., Schrittwieser, J., Simonyan, K. et al. Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge. Nature 550, 354–359 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature24270

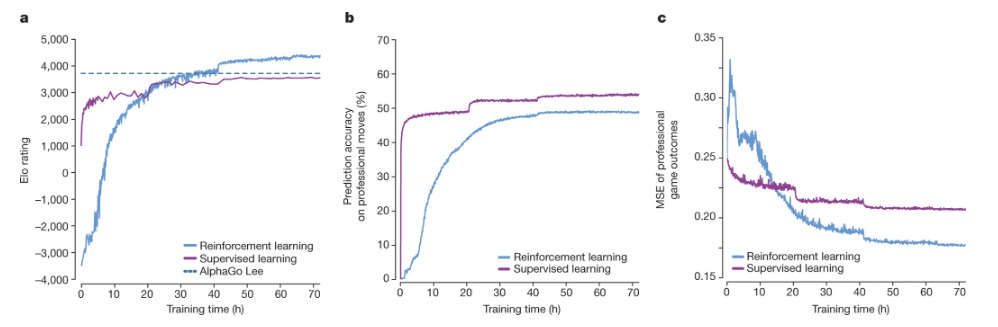

From the above figure, we can see that the algorithm can surpass AlphaGo after only ~40h of training. Interestingly enough, we can see that AlphaGo Zero is not really good at predicting moves, but quite good at predicting game outcome. A supervised learning version of the algorithm is shown for comparison. Because it manages to outperform AlphaGo (and therefore the best human player, assuming ELO is transitive), the results seem to imply that AlphaGo Zero learns to play differently than human players (which could explain moves 37 and 78).

AlphaZero

Still on a quest to remove priors, Deepmind then released AlphaZero. AlphaZero keeps the same model and overall training process as AlphaGo Zero but removes some components that do not translate well to other games. Notable changes include:

- Removal of data augmentation (rotating and flipping boards) that was done by AlphaGo Zero because it would create impossible configurations for Chess and Shogi

- Opponents for self-play are now simply the exact same neural network instead of a roster of previous versions of the algorithm

- AlphaZero reuses the same hyperparameters but one (exploration is dependent on the number of valid moves) for all games

Silver, David, et al. “Mastering Chess and Shogi by Self-Play with a General Reinforcement Learning Algorithm.” ArXiv:1712.01815 [Cs], Dec. 2017. arXiv.org, http://arxiv.org/abs/1712.01815

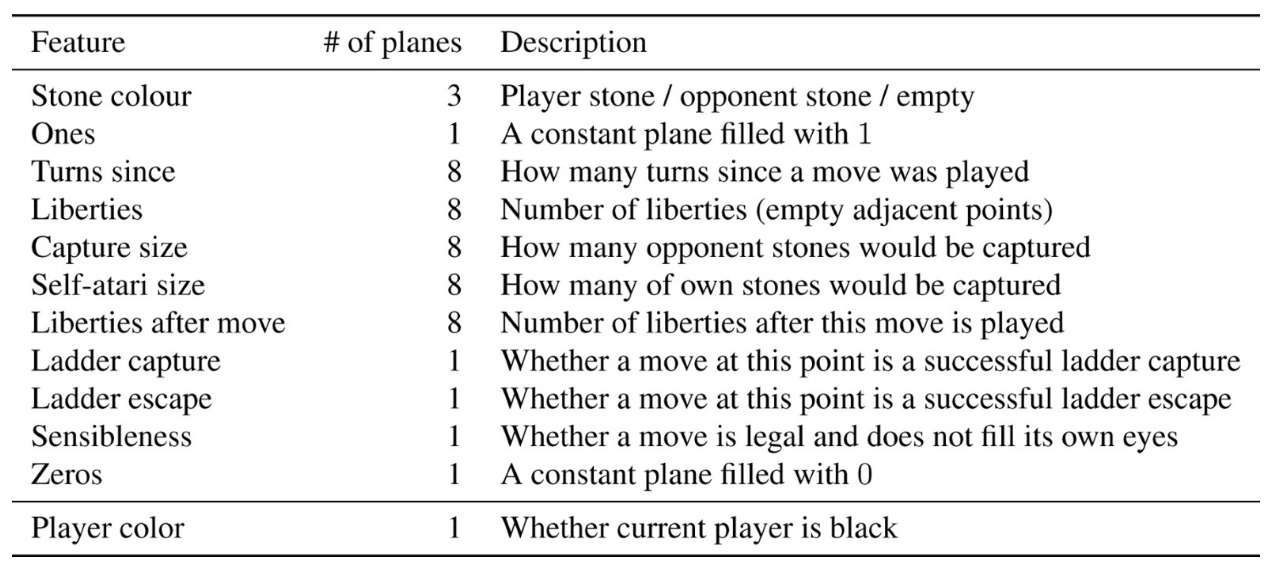

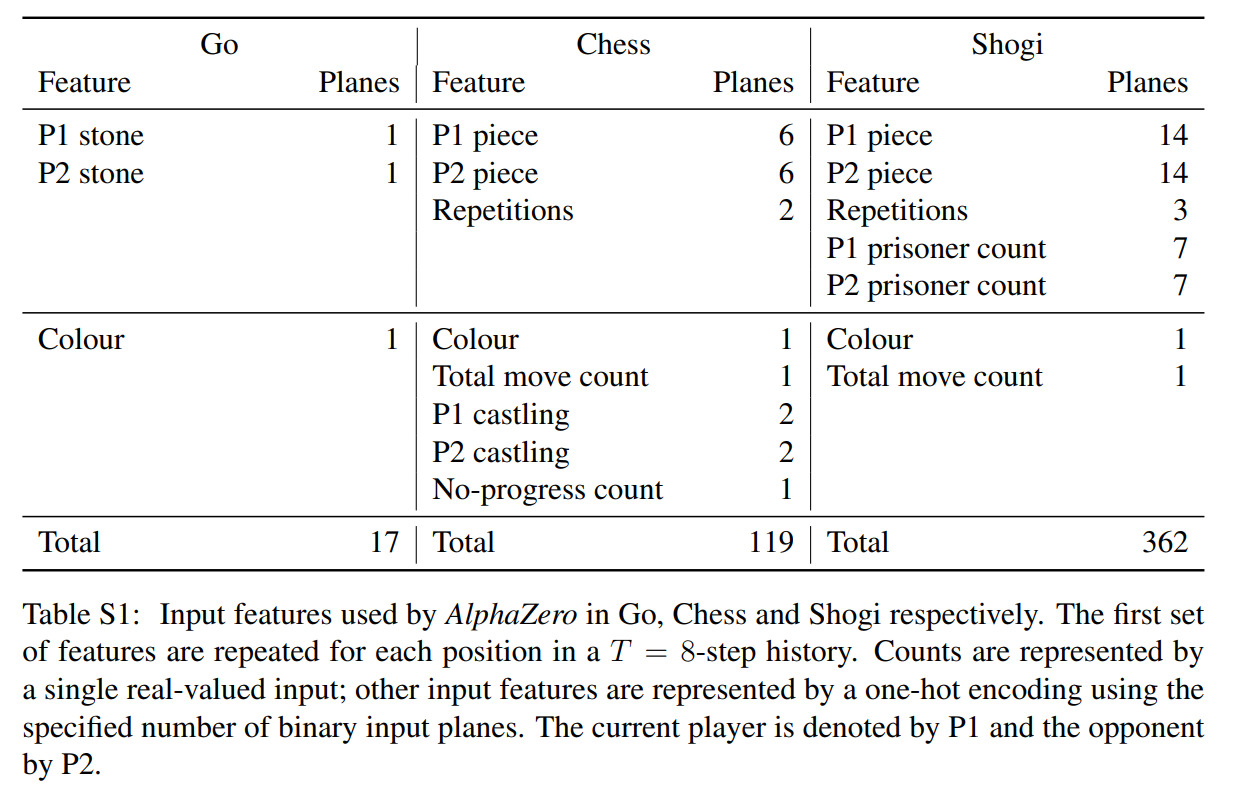

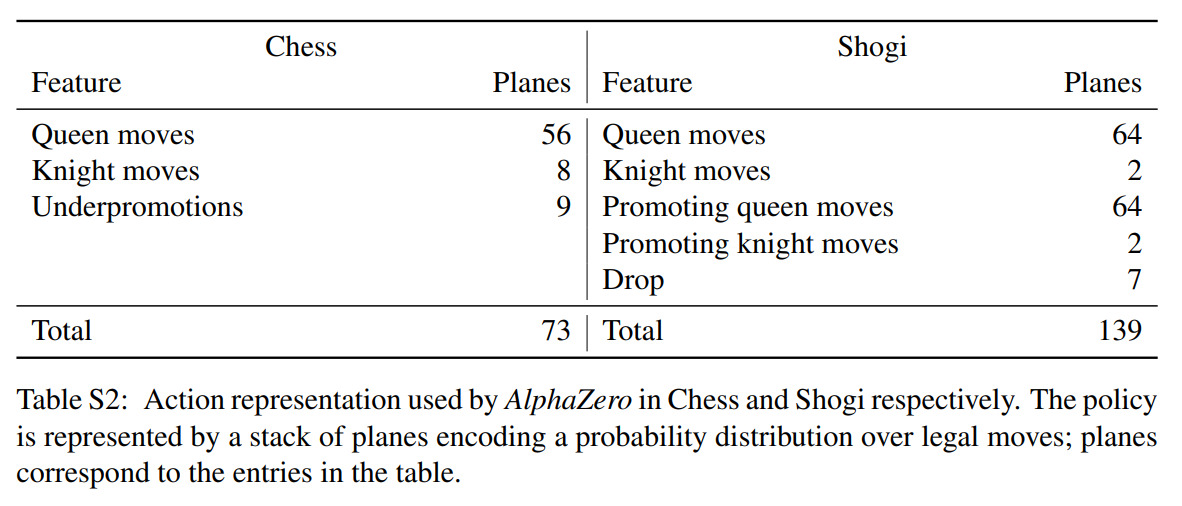

Handcrafted features make a return, as shown above, and action probabilities now must take a different form, also shown above.

Silver, David, et al. “Mastering Chess and Shogi by Self-Play with a General Reinforcement Learning Algorithm.” ArXiv:1712.01815 [Cs], Dec. 2017. arXiv.org, http://arxiv.org/abs/1712.01815

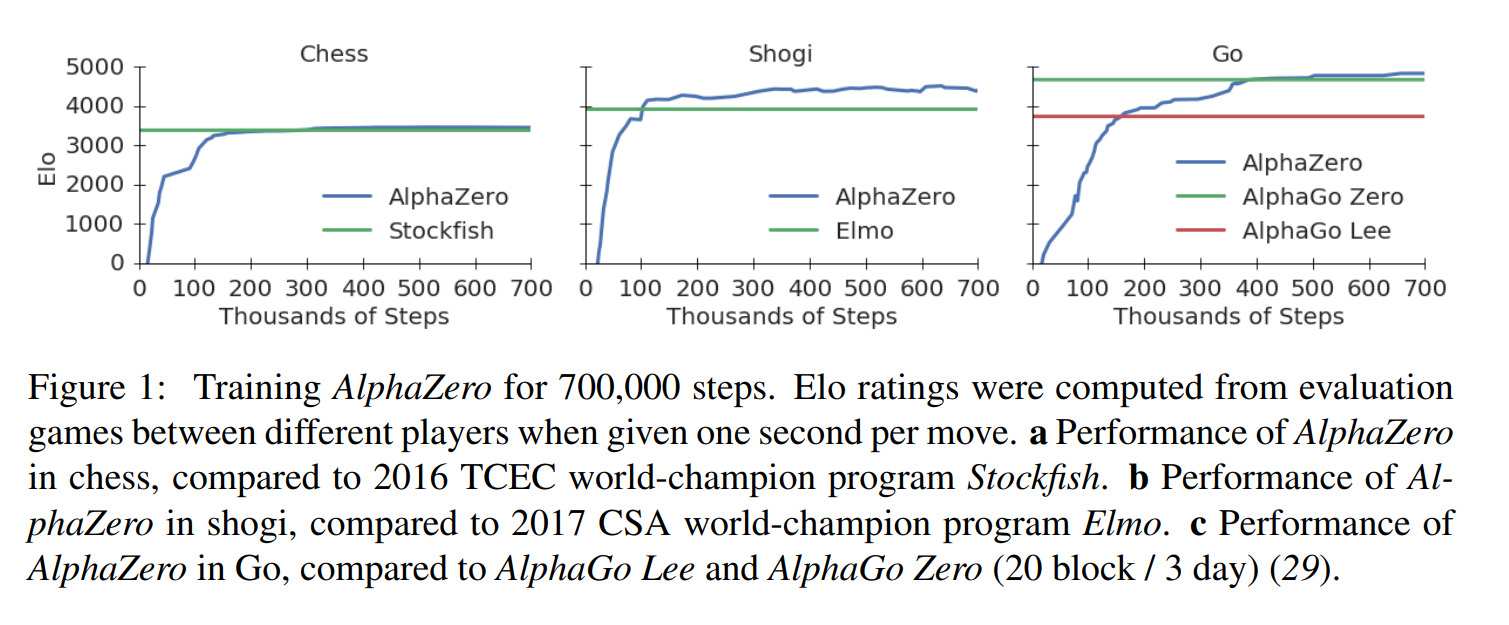

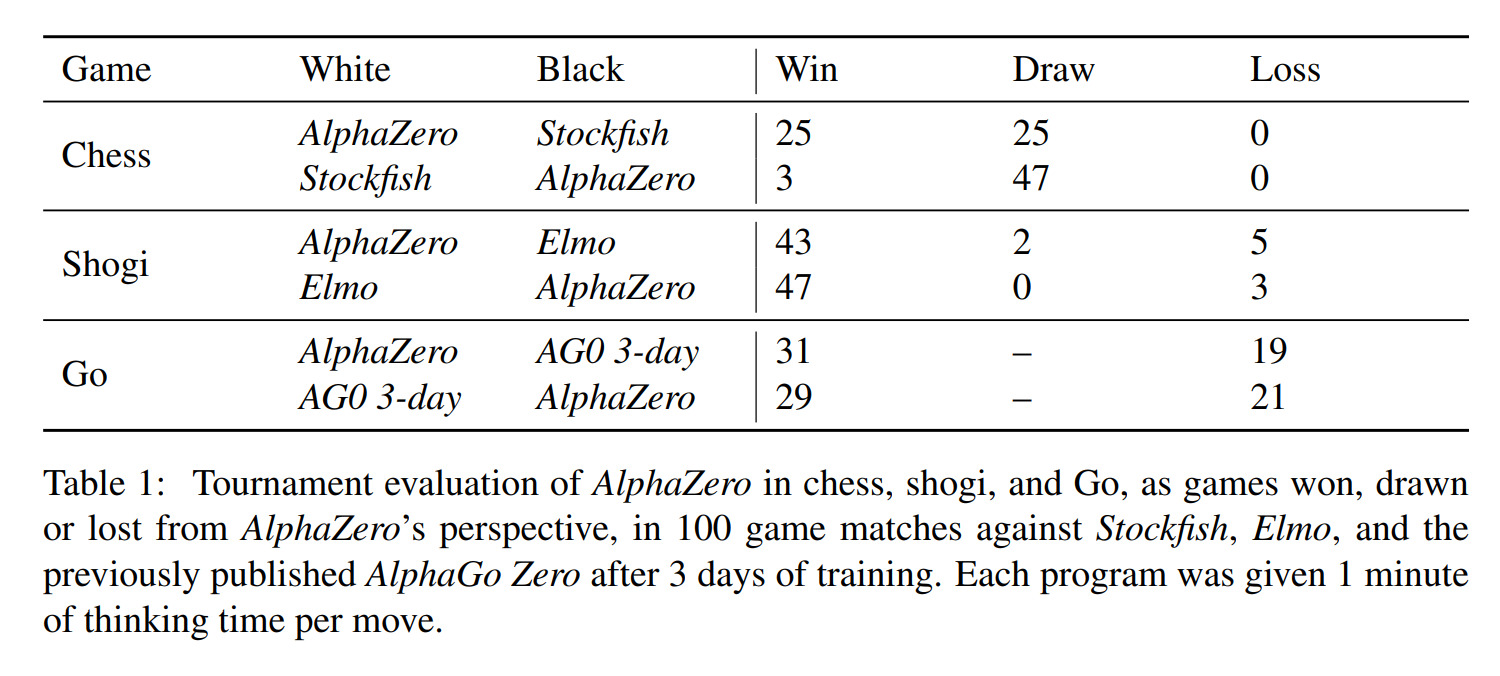

Above are shown results from the training process. We can observe that AlphaZero manages to defeat both AlphaGo Zero as well as game-specific algorithms.

MuZero

Chess, Shogi and Go are games that can easily offer a perfect simulator as their rules are simple and well defined. However, this is not the case for most real-world scenarios such as robotics or video games. Model-based reinforcement learning tries to tackle this problem by learning a simulator and then allowing planning using this learned simulator.

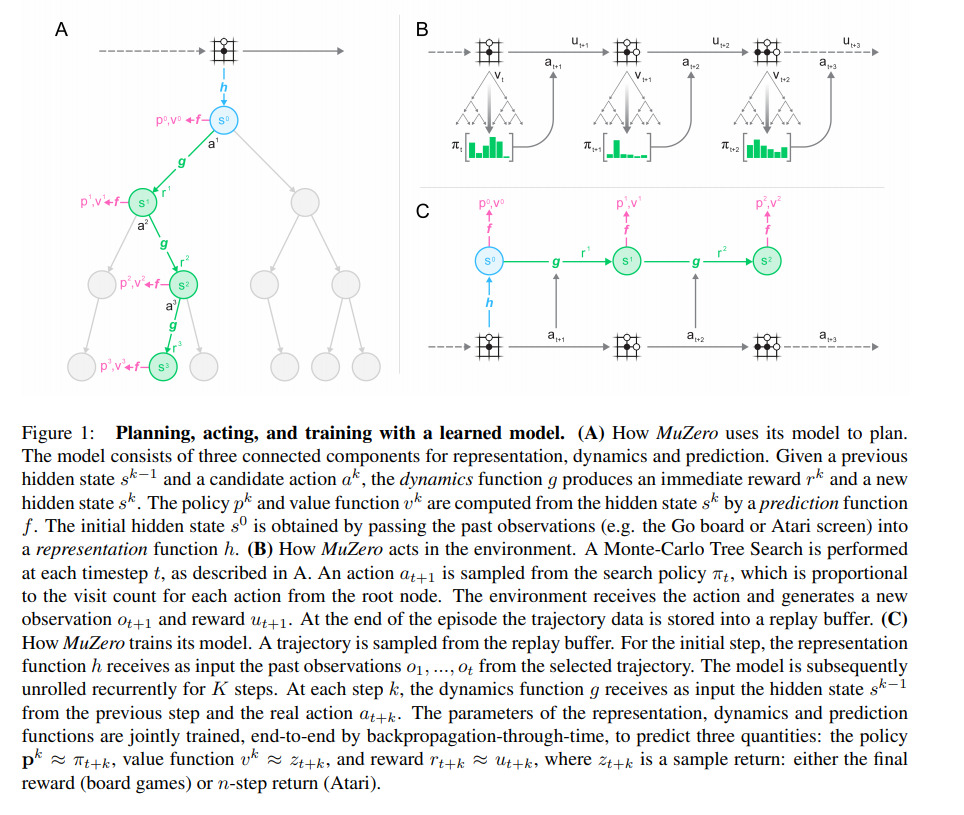

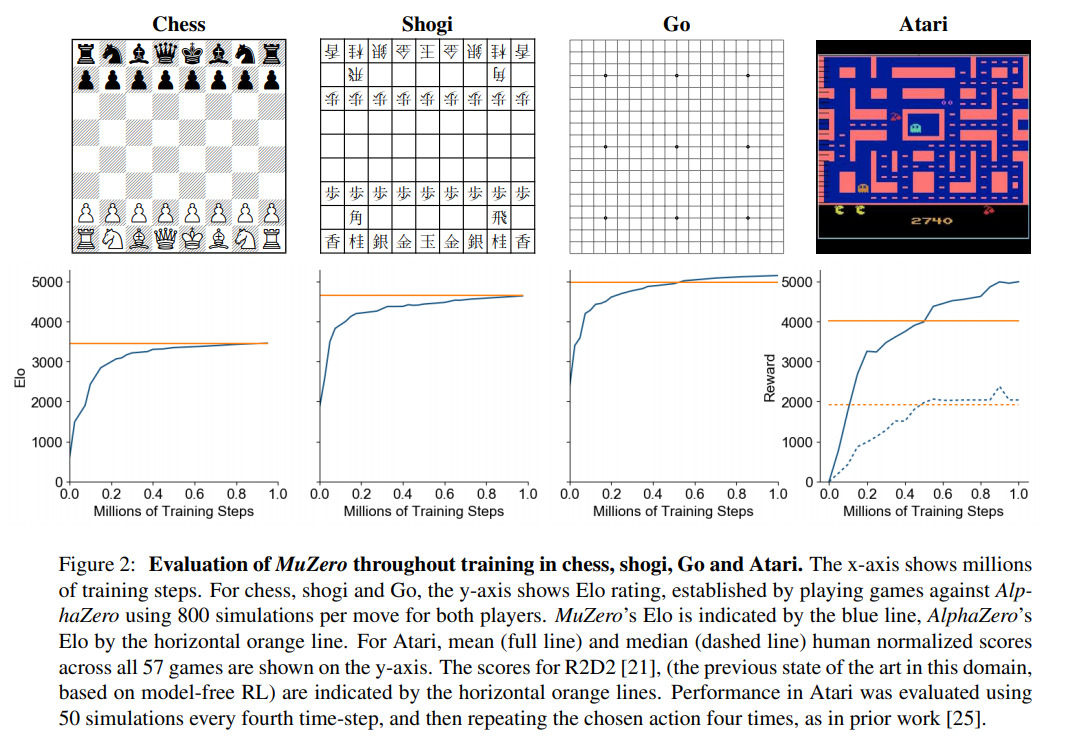

MuZero improves upon AlphaZero by learning a simulator and extending the tree-search algorithm to the general reinforcement learning setting of a single agent learning from discounted non-sparse rewards, allowing the algorithm to master the Atari Learning Environment suite while maintaining superhuman performance on previous games. In the following slides, subscript \(k\) defines simulated timesteps, and \(t\) defined real timesteps.

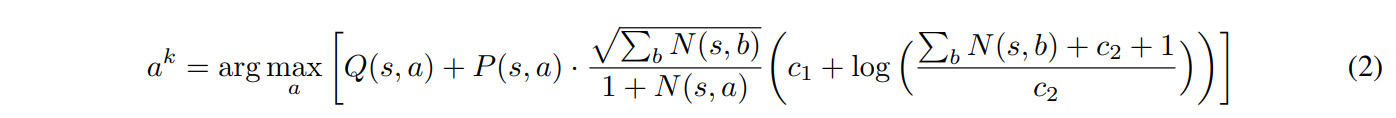

To allow for the general reinforcement learning setting, the heuristic for exploring the tree is defined as

with

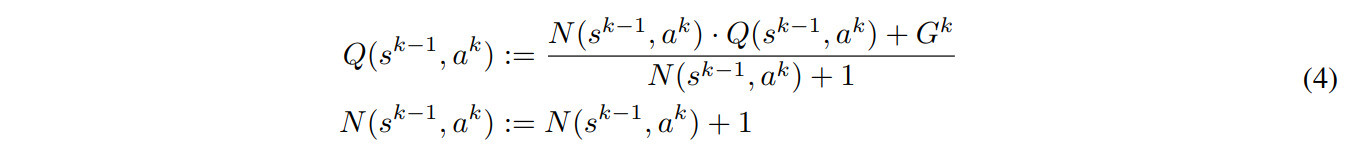

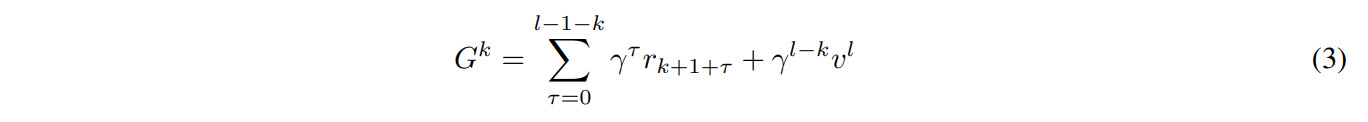

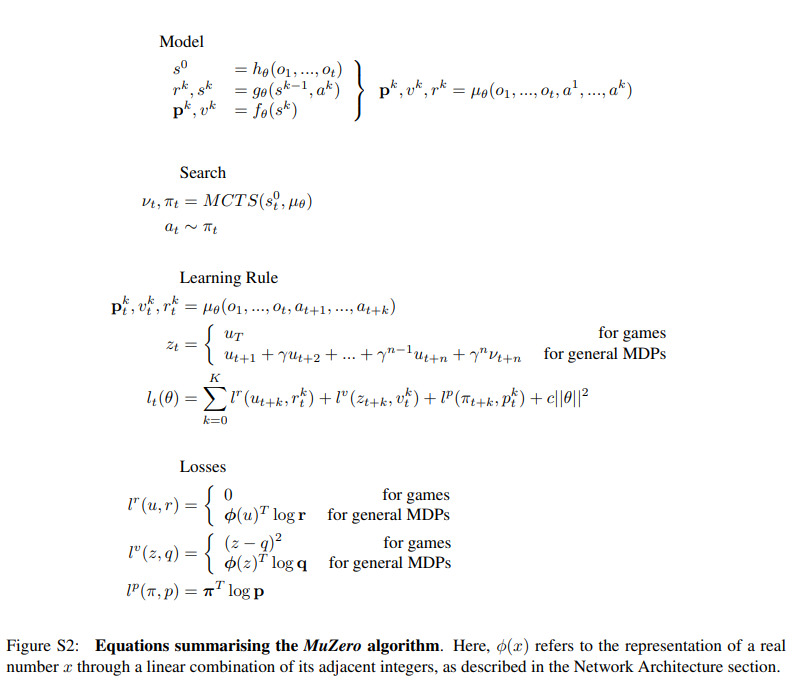

A good overview of the different models and losses is given in the paper’s supplementary materials:

One thing to note is that the hidden state \(s\) is never explicitly trained to match the real observations \(o\). The dynamics model \(g\) only has to match the reward output by the environment. This allows them to have \(s\) be a lower-dimensional representation of the state, facilitating the training of other components.

Above are the results for the training on all four domains. We can see that MuZero manages to outperform or match the performances of AlphaZero on all three board games as well as exceed the performances of then-state of the art R2D2 on Atari.

Conclusions

AlphaGo was a turning point in the public’s vision of artificial intelligence, breaking the “last barrier” against human intelligence. In subsequent papers, Deepmind showed that the method could be generalized to more than Go without loss of performance.

References

Links

-

Coulom R. (2007) Efficient Selectivity and Backup Operators in Monte-Carlo Tree Search. In: van den Herik H.J., Ciancarini P., Donkers H.H.L.M.. (eds) Computers and Games. CG 2006. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 4630. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-75538-8_7 ↩