BEAR (Bootstrapping Error Accumulation Reduction)

Highlights

- Analysis of error accumulation in the bootstrapping process due to out-of-distribution inputs in off-policy offline reinforcement learning

- A principled algorithm called bootstrapping error accumulation reduction (BEAR) to control bootstrapping errors

Introduction

Reinforcement Learning (RL) algorithms are often criticized-for and limited-by their heavy need for data collection. Recent off-policy RL methods have demonstrated sample-efficient performance on complex tasks in robotics and simulated environments, but these methods can still fail to learn when presented with arbitrary off-policy data without the opportunity to collect more experience from the environment where supervised algorithms would thrive.

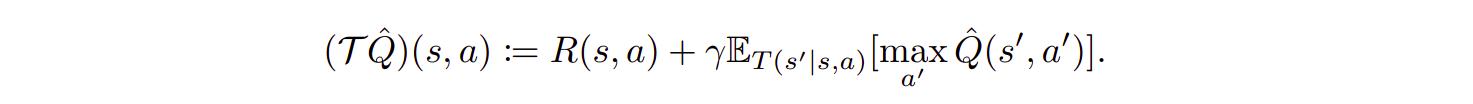

Q-learning learns the optimal state-action value function \(Q^*(s,a)\), which represents the expected cumulative discounted reward starting in \(s\) taking action \(a\). Q-learning algorithms are based on iterating the Bellman optimality operator \(\tau\), defined as

Reinforcement learning then corresponds to minimizing the squared difference between the left-hand side and right-hand side of this equation, also referred to as the mean squared Bellman error (MSBE):

In practice, an empirical estimate of \(\tau\hat{Q}\) is formed with samples. In large action spaces (e.g., continuous), the maximization \(max_{a'}Q(s', a')\) is generally intractable. Actor-critic methods address this by additionally learning a policy \(\pi\) that maximises the Q-function.

Out-of-Distribution Actions in Q-Learning

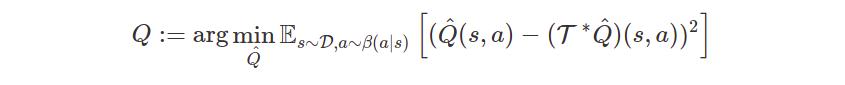

Q-learning methods often fail to learn on static, off-policy data.

The targets for the regression are calculated by maximizing or computing the expectation of the Q-value with respect to the action at the next state. This is called bootstrapping: Regressing towards your own predictions. However, the q-value estimates are only reliable for actions from the behavior policy: the training distribution/replay buffer. Evaluating next states according to actions that lie far outside the training distribution (because they are from the current policy, not the behavioral policy) means propagating errors in the Q-function estimator, which are called bootstraping errors. These action are called out-of-distribution actions.

The agent is unable to correct these bootstrapping errors as it cannot gather ground truth by exploring the environment, which leads to Q-values not converging to the correct values and making to final performance that is much worse than expected.

Behavior cloning methods which only train on actions in the dataset, even those who assign different weights to action like AWR1, won’t produce OOD actions but may fail to recover the optimal policy if trajectories observed are suboptimalor do not cover the entirety of the action distribution.

Dynamic programming methods may seem appealing because they will constrain the trained policy distribution to lie close to the behavior policy that generated the dataset. However, if the dataset was generated by a non-expert, this solution might not be optimal.

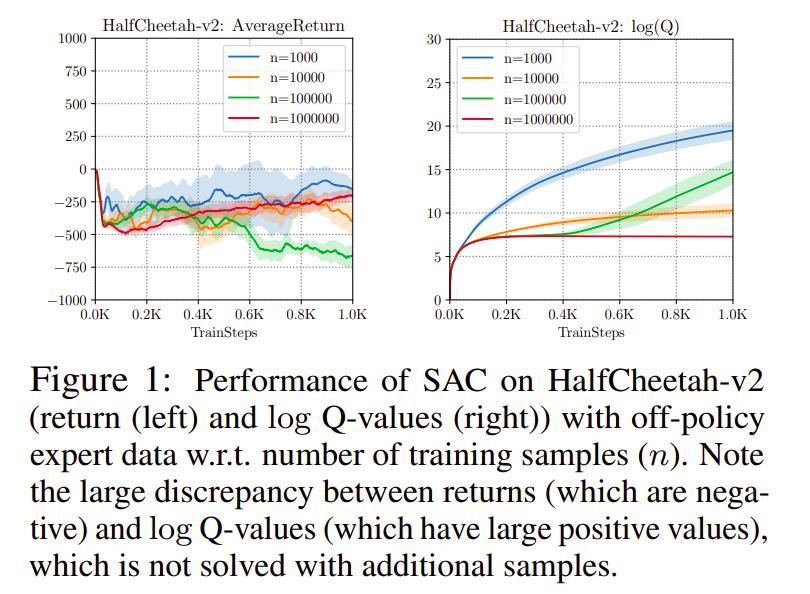

The question to be asked is: Which policies can be reliably used for backups without backing up OOD actions?

Bootstrapping Error Accumulation Reduction (BEAR)

Matching the distribution of actions in the training set may not lead to recovering the optimal policy. For example, for a training set consisting of uniform-at-random actions, a distribution matching algorithm will recover a highly stochastic policy while the optimal policy may be deterministic. A support-matching algorithm, however, will only constrain the learned policy to lie with the support of the distribution. Simply put, this will only constrain the learned policy to place non-zero probability mass on actions with non-negligible behavior policy density.

To enforce that the learned policy satisfies the support contraint, the authors use the sampled Maximum Mean Discrepancy (MMD) distance between actions as a measure of support divergence. The blog post2 as well as the article provide a good explanation of how the MMD is calculated.

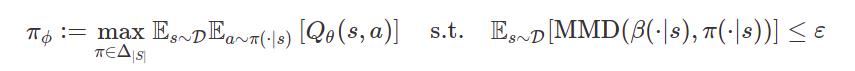

The new (constrained-)policy improvement step in an actor-critic setup is given by:

(alg.1)

(alg.1)

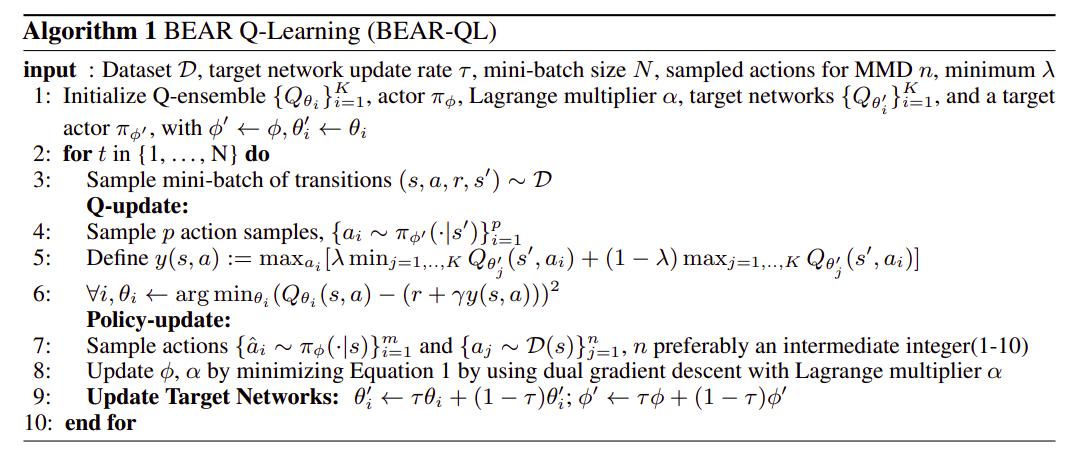

with the full algorithm being

Results

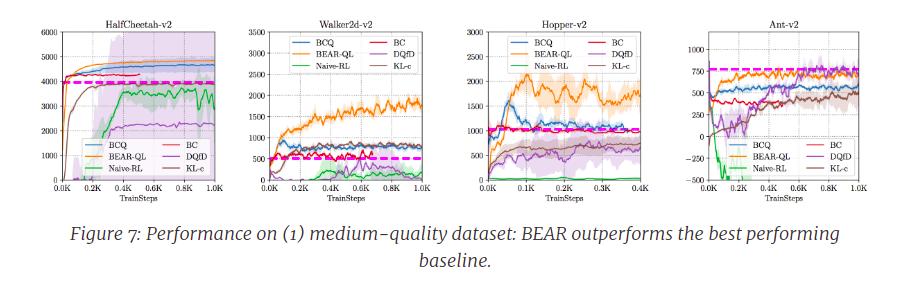

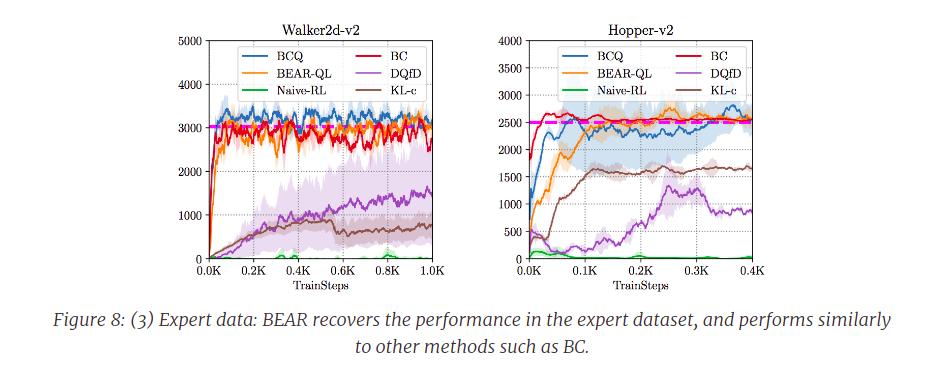

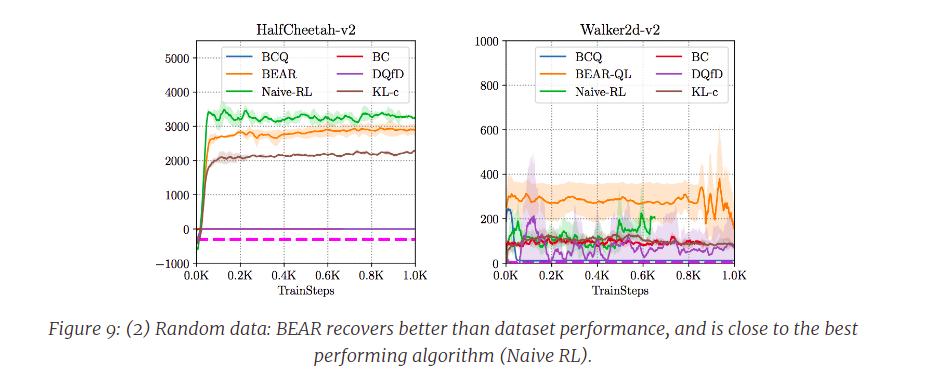

[The authors] evaluated BEAR on three kinds of datasets generated by – (1) a partially-trained medium-return policy, (2) a random low-return policy and (3) an expert, high-return policy. […] For each dataset composition, [the authors] compare BEAR to a number of baselines including BC, BCQ, and deep Q-Learning from demonstrations (DQfD)

Where the purple dotted straight line means the average reward in the corresponding dataset.

Conclusions

In general, [the authors] find that BEAR outperforms the best performing baseline in setting (1), and BEAR is the only algorithm capable successfully learning a better-than-dataset policy in both (2) and (3). We show some learning curves below. BC or BCQ type methods usually do not perform great with random data, partly because of the usage of a distribution-matching constraint as described earlier.

References

- Code: https://github.com/aviralkumar2907/BEAR

- Slides: https://sites.google.com/view/bear-off-policyrl

-

Advantage-Weighted Regression, https://vitalab.github.io/article/2019/10/02/AWR.html ↩