Stealing Machine Learning Models via Prediction APIs

Highlights

- Simple equation-solving model-extraction attacks for simple ML models

- Model extraction attacks against models that output only class labels

Introduction

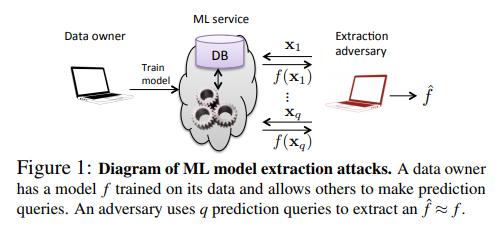

Machine learning (ML) models may be deemed confidential due to their sensitive training data, commercial value, or use in security applications. Increasingly often, confidential ML models are being deployed with publicly accessible query interfaces. ML-as-a-service (“predictive analytics”) systems are an example: Some charge users for access on a pay-per-query basis. The tension between model confidentiality and public access motivates [the authors’] investigation of model extraction attacks. In such attacks, an adversary with black-box access, but no prior knowledge of an ML model’s parameters or training data, aims to duplicate the functionality of (i.e., “steal”) the model

The goal here is to, after gaining access to a black-box target model \(f\), train a model \(\hat{f}\) that closely approximates or even matches \(f\). Matching here implies that, with \(f_i(x)\) being either the prediction over \(x\) for the \(i^{th}\) class or the confidence score associated with the \(i^{th}\) class, \(f_i(x) \equiv \hat{f}_i(x)\) \(\geq\) 99.9% of times.

Methods and results

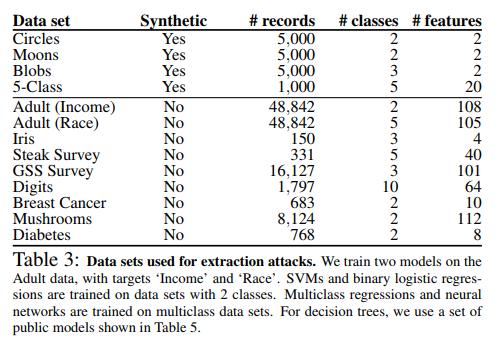

Data

Extraction with Confidence Values

First off, extraction attacks on prediction APIs that return confidence values. Here, \(f(x) \in [0,1]^c\) where \(c\) is the number of classes. For simple enough models, equation-solving attacks can be used to directly infer the model’s parameters. For example, in the case of a binary logistic regression (LR) with parameters \(w \in R^d\) that outputs a probability \(f_1(x) = \sigma(wx)\), and given a oracle sample \((x, f(x))\), we get a linear equation \(wx = \sigma^{-1}(f_1(x))\) and thus, only \(d+1\) linearly independent samples can be used to recover the parameters.

For all the datasets shown in table 3, the authors could train a model and extract it in \(d+1\) predictions with 100% confidence error. For these models, the attack only required 41 queries on average and 113 at most.

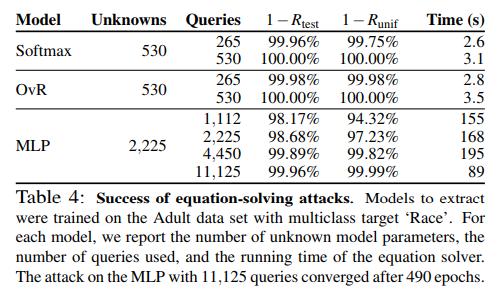

The authors also took a shot a attacking multiclass LR (MLR) models, such as softmax and one-vs-rest (OvR) models. MLRs models are parametrized by \(w \in R^{cd}\), and no longer provide linear equation systems to be solved. However, by minimizing an appropriate loss function, such as the logistic loss, the optimization problem becomes convex and can converge to a global minimum. This also applies to multi-layer perceptrons (MLP) which are parametrized by \(w \in R^{dh+hc}\) where \(h\) is the number of hidden layers. However in the case of MLPs, the loss function is no longer convex and the optimization may not converge to a global minimum.

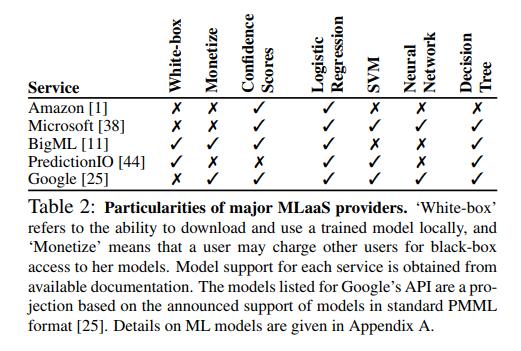

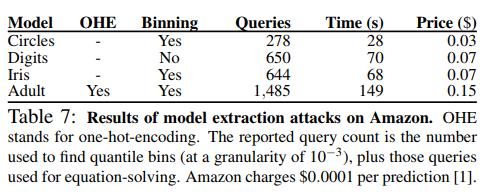

Online Model Extraction Attacks

The authors then tried to extract models setup online on BigML and Amazon AWS. BigML uses decision tree which will not be adressed in this review. Amazon, however, allows users to upload their data and then Amazon will perform feature extraction and then train a model on these features.

The problem now is to find what features were extracted and which model was used. However, AWS does support “partial input”, where you can send an image for prediction which does not have some of the extracted features and still get a result. Without going into details, the authors were able to reverse-engineer the features and still get a copy of the model with 100% matches.

In all the attacks, the authors were able to learn about the model’s class, the enabled feature extractors and hyperparameters through the ML service AWS’s documentation. In a real world scenario, an attacker could narrow down its hyperparameter search through similar techniques and cross-validation.

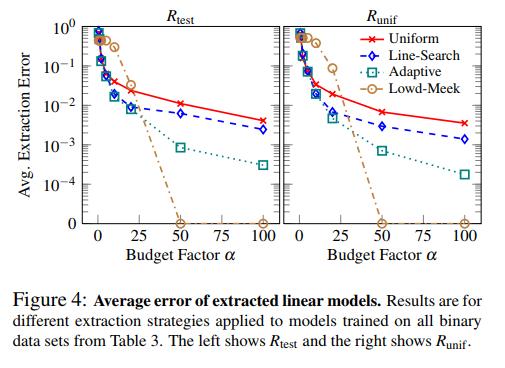

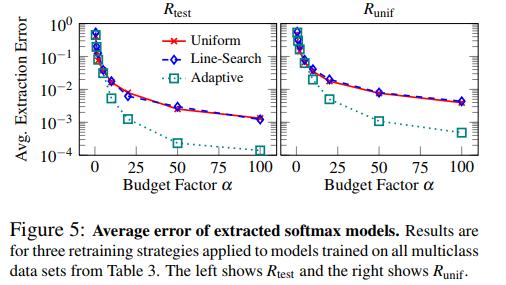

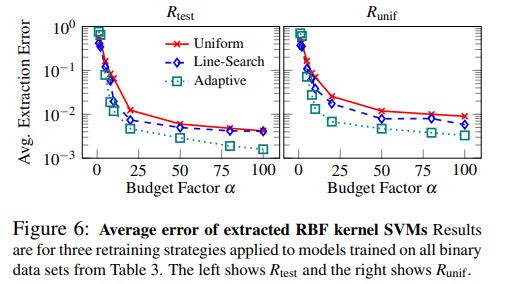

Extraction Given Class Labels Only

Without going into details, the authors wanted to see if they could extract the model through only class predictions. The general strategy is called retraining, where the authors query the models with data points that are close to \(\hat{f}\)’s decision boundary.

where \(\alpha\) is the budget, or multiplier of \((d+1)\) data points used.

Prevention from such attacks

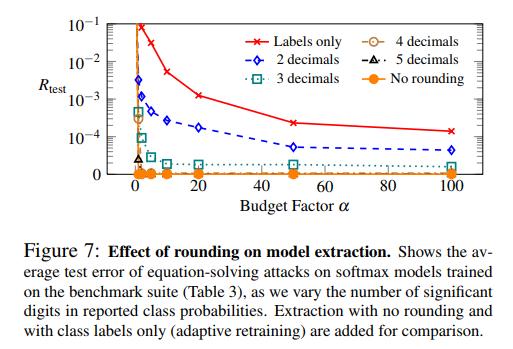

The authors suggest some countermeasures to such attacks, such as rounding off the prediction’s accuracy. The impacts of rounding the accuracy (or only providing class labels) is reported below

They also mention using ensemble methods, as recovering \(n\) times model parameters is much more costly and only one set of model parameters.

Conclusions

[The authors] demonstrated how the flexible prediction APIs exposed by current ML-as-a-service providers enable new model extraction attacks that could subvert model monetization, violate training-data privacy, and facilitate model evasion.

Remarks

- All the attacks were done on models set up by the authors themselves so as not to potentially harm anyone.

- The authors also attacked decision tree models and Kernel SVMs with success. They also performed model inversion attacks to recover training data with variable success.

- All the attacks presumed the attackers know the models’ architectures.

- All the attacks are heavily dependant on the number of parameters and, therefore, modern models might prove to be too costly for these attacks.