On the Utility of Learning about Humans for Human-AI Coordination

Highlights

- Self-play algorithms use (near) optimal solutions when playing together against humans

- However, RL algorithms do not perform as well when playing with humans

- Training them to perform with humans makes them perform better with humans

Introduction

An increasingly effective way to tackle two-player games is to train an agent to play with a set of other AI agents, often past versions of itself. This powerful approach has resulted in impressive performance against human experts in games like Go, Quake, Dota, and Starcraft.

However, these agents were all trained via self-play and never encounter humans during training and therefore undergo serious distributional shift. How do they not fail catastrophically when put against human players ? The authors hypothesize that it is because of the competitive nature of these games. Indeed, even with a simple Minimax1 policy, if a human makes a suboptimal move, the AI agent can only beat them even more soundly.

However, one could argue that the ultimate goal of AI is to produce collaborative agents rather than competitive ones. Recent results in games like Dota2 and Capture the Flag2. While the results of these experiments seems to point towards self-play extending nicely to cooperation, the authors argue that the nice results come from the agents’ own abilities and not coordination with humans.

Methods

The authors proposed three testable hypotheses and devised a new environment to test them. The hypotheses go as follows:

H1. A self-play agent will perform much more poorly when partnered with a human (relative to being partnered with itself).

H2. When partnered with a human, a human-aware agent will achieve higher performance than a self-play agent, though not as high as a self-play agent partnered with itself.

H3. When partnered with a human, a human-aware agent will achieve higher performance than an agent trained via imitation learning.

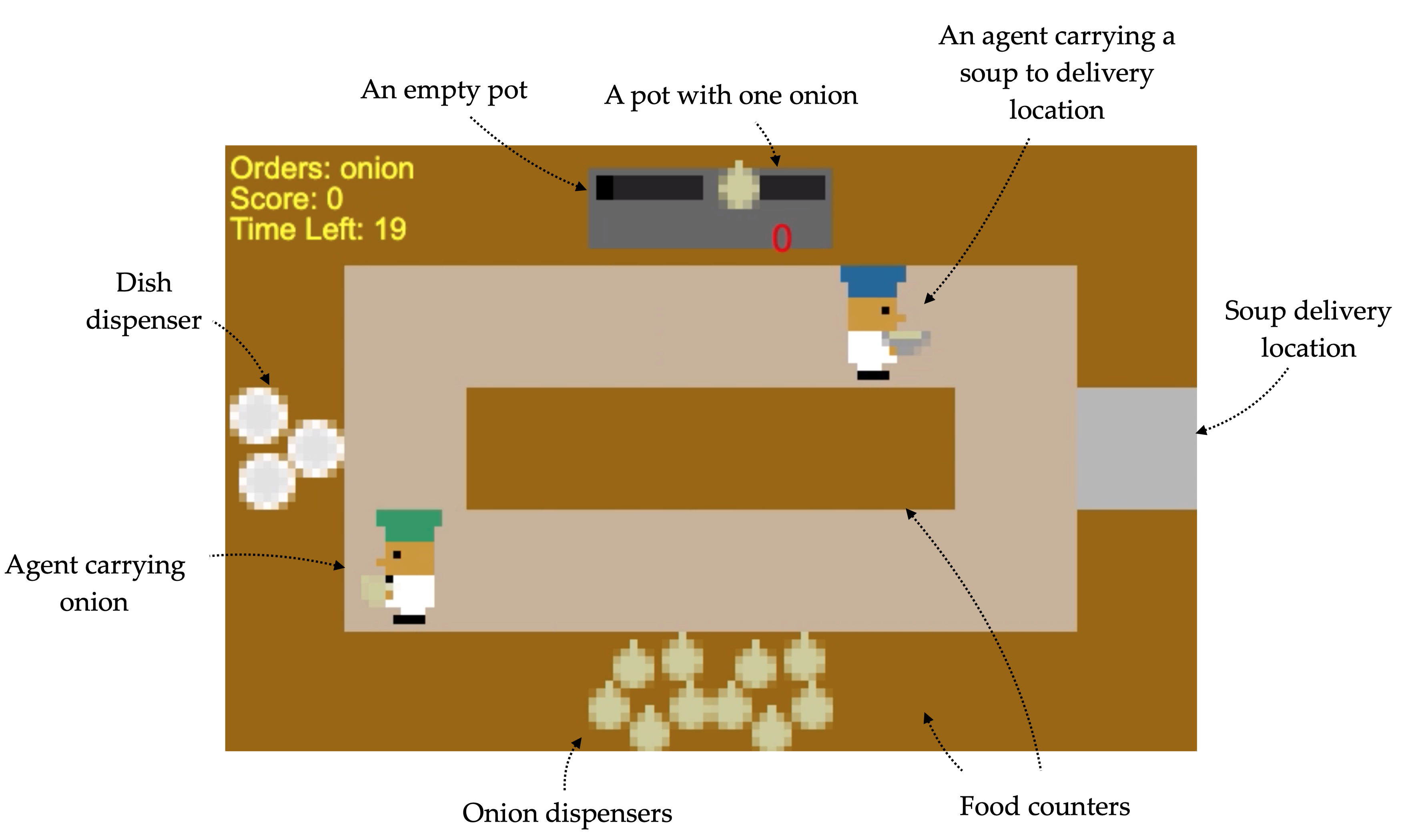

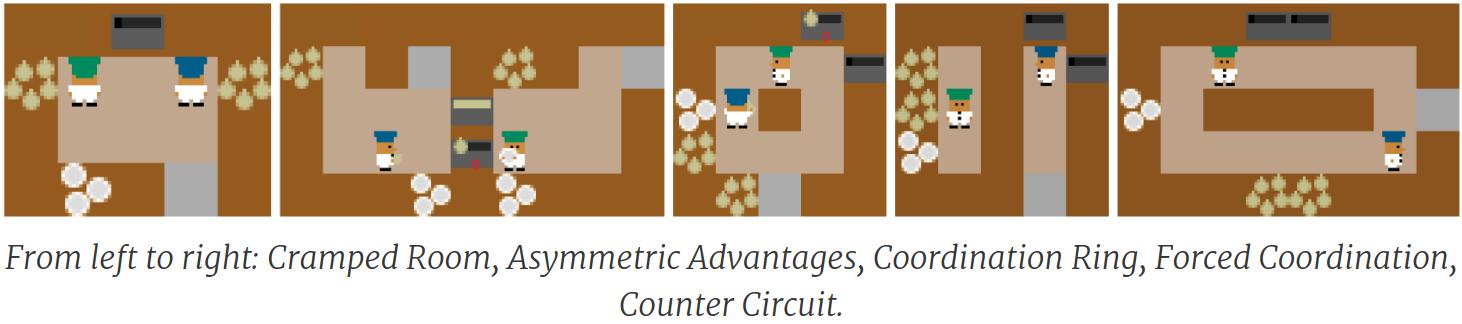

They also created the Overcooked environment, based on the video game of the same name, to measure human-agent cooperation. The environment has five different possible scenarios, as pictured above, all with the same goal: Cooking onion soup and delivering it to the serving location.

Agents should learn how to navigate the map, interact with objects, drop the objects off in the right locations, and finally serve completed dishes to the serving area. All the while, agents should be aware of what their partner is doing and coordinate with them effectively.

To train the agents, the authors gathered 16 human-human trajectories for each layout. They then used behavior cloning (BC) to create the \(BC\) model (training time) and \(H_{proxy}\) model (test time) to remove the need for human interactions because involving humans in the training loop would be infeasible.

The authors considered two DRL algorithms, PPO and PBT4, to be trained via self-play(SP) and one planning algorithm. The planning algorithm pre-computes the (near) optimal motion plan by searching every possible starting and goal states for agents, bundles actions into high-level actions such as “get an onion” and use the motion plan to compute costs for each action. At runtime, A* is used to search the next best action to do according to the agent’s current state.

Results

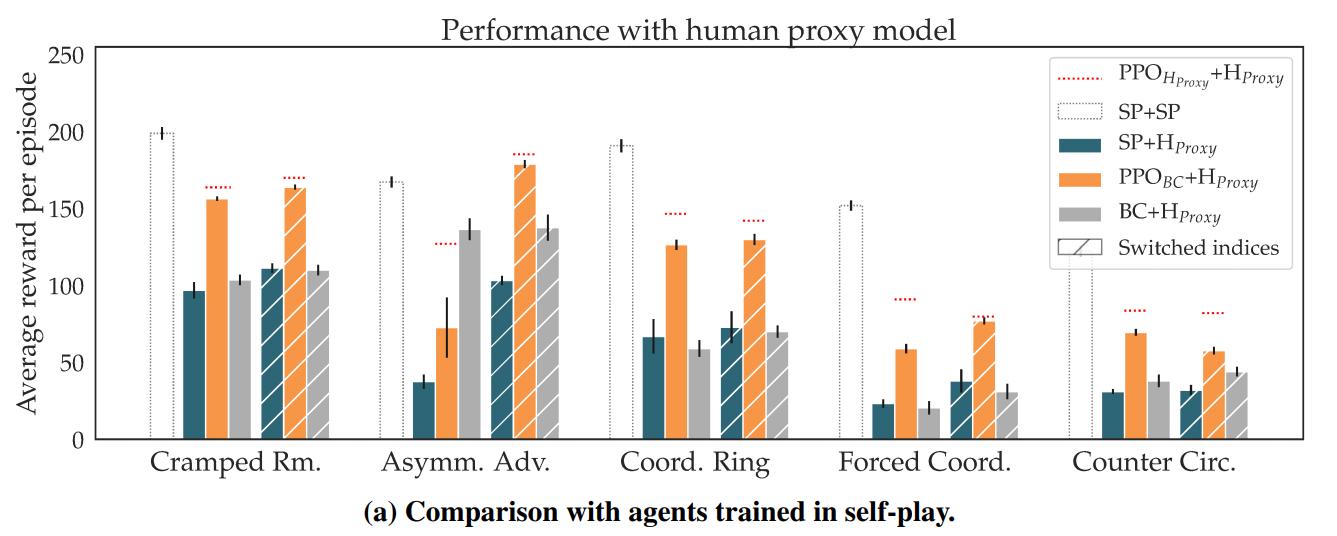

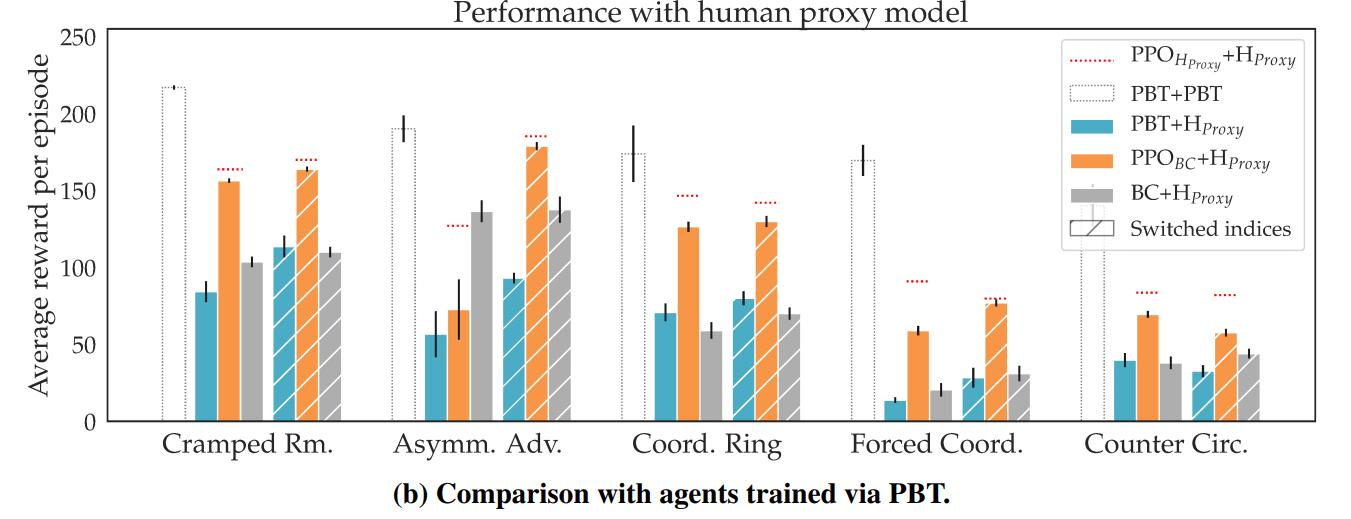

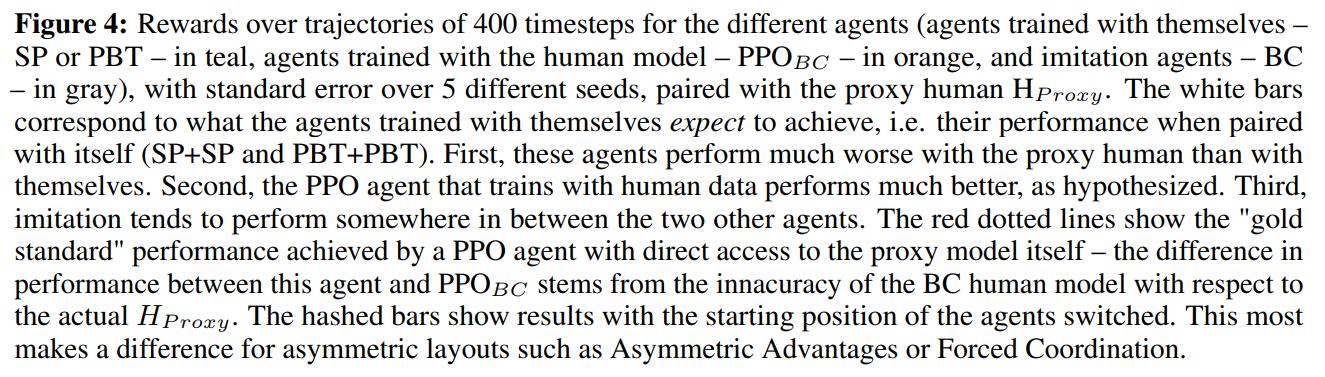

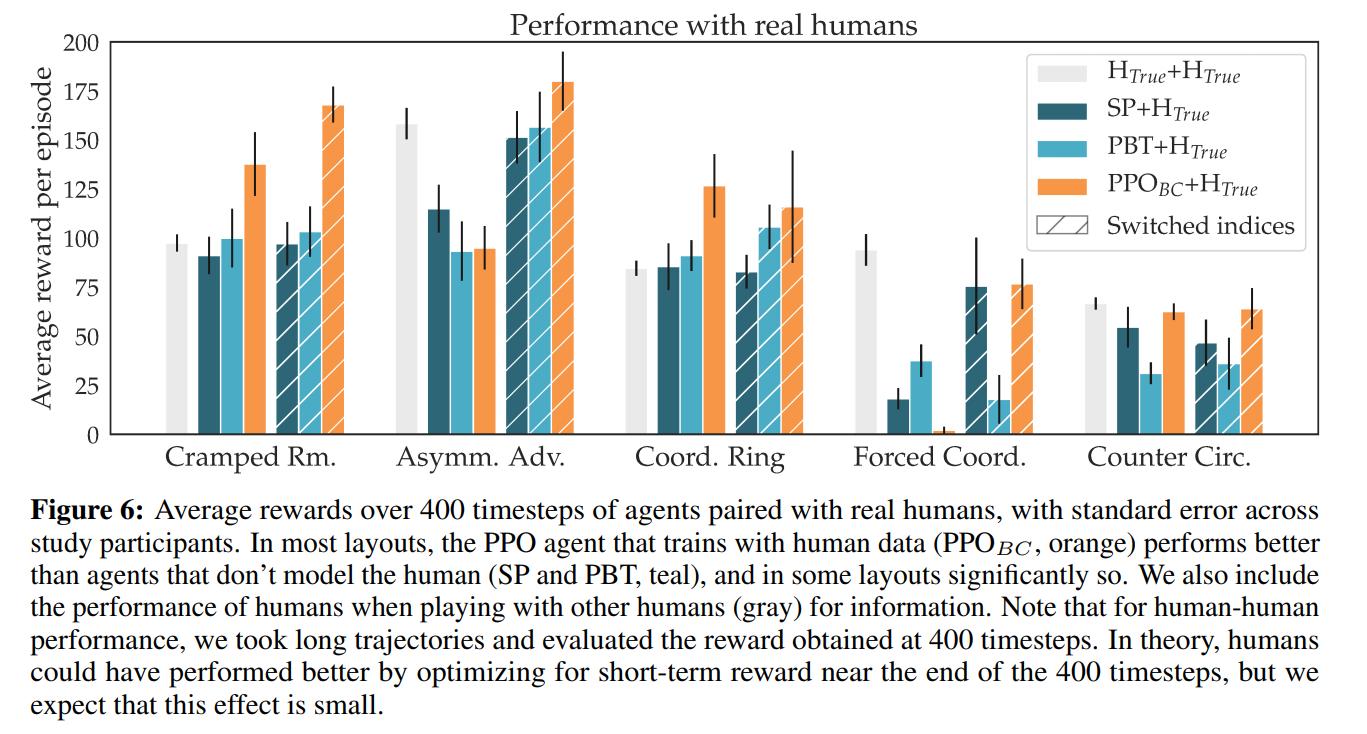

H1 is clearly supported: self-play agents perform worse with humans than with themselves. H2 is also supported: \(PPO_{BC}\) is statistically significantly better than \(SP\) or \(PBT\), though the effect is much less pronounced than before. Since their method only beats teams of humans in 5/10 configurations, the data is inconclusive about H3.

Conclusions

While agents trained via general DRL algorithms in collaborative environments are very good at coordinating with themselves, they are not able to handle human partners well, since they have never seen humans during training.

Agents that were explicitly designed to work well with a human model, even in a very naive way, achieved significantly better performance. Qualitatively, we observed that agents that learned about humans were significantly more adaptive and able to take on both leader and follower roles than agents that expected their partners to be optimal (or like them).

Remarks

The authors have not accounted for communication between players, which Starcraft or Dota players use extensively.

Additional links

References

[1]: Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001) [1994], “Minimax principle”, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

[2]: OpenAI. How to train your OpenAI Five. 2019. https://openai.com/blog/how-to-train-your-openai-five/.

[3]: Max Jaderberg, Wojciech M. Czarnecki, Iain Dunning, Luke Marris, Guy Lever, Antonio Garcia Castañeda, Charles Beattie, Neil C. Rabinowitz, Ari S. Morcos, Avraham Ruderman, Nicolas Sonnerat, Tim Green, Louise Deason, Joel Z. Leibo, David Silver, Demis Hassabis, Koray Kavukcuoglu, and Thore Graepel. Human-level performance in 3d multiplayer games with population-based reinforcement learning. Science, 364(6443):859–865, 2019. ISSN 0036-8075. doi: 10.1126/science.aau6249. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/364/ 6443/859.

[4]: Max Jaderberg, Valentin Dalibard, Simon Osindero, Wojciech M Czarnecki, Jeff Donahue, Ali Razavi, Oriol Vinyals, Tim Green, Iain Dunning, Karen Simonyan, et al. Population based training of neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.09846, 2017.