Evaluating the Search Phase of Neural Architecture Search

Highlights

- A NAS evaluation framework that includes the search phase

- On average, a random policy outperforms state-of-the-art NAS algorithms

- Results and candidate rankings of NAS algorithms do not reflect the true performance of candidate architectures

- Weight sharing hurts the training of good architectures

Introduction

Since the dawn of time, mankind has tried to find the best neural network architecture to solve its problems. Neural Architecture Search (NAS) allows the user to automatically find the architecture giving the best validation results on the selected dataset.

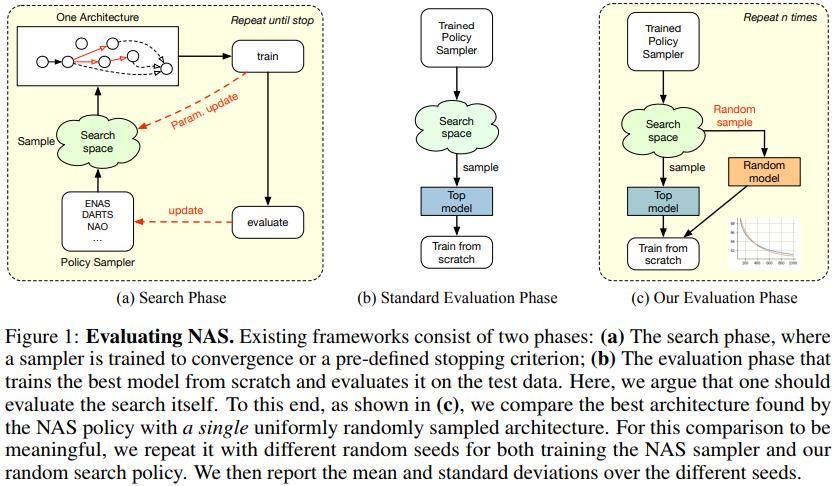

A typical NAS technique has two stages: the search phase, which aims to find a good architecture, and the evaluation one, where the best architecture is trained from scratch and validated on the test data.

Since the search space contains billions of architectures, the fact that NAS algorithms produce networks that achieve state-of-the-art results on the downstream tasks is typically attributed to the search algorithms these methods rely on. While this might seem intuitive, this assumption has never been verified; the effectiveness of the search procedure is never directly evaluated.

Because training a whole set of architectures is expensive, NAS algorithms typically use weight sharing, where all the selected architectures are trained in parallel and their weights are shared, to alleviate the training costs.

The authors want to evaluate the search phase of NAS algorithms. More specifically, they want to evaluate the impact of the search space for architectures and weight sharing.

Methods

The authors compare three state-of-the-art NAS algorithms to a random architecture sampler. The chosen algorithms are ENAS, which uses reinforcement learning; DARTS, which uses gradient descent, and NAO, which uses performance prediction. More details about theses algorithms are available in Appendix B.

Data

The authors tested on the Penn Tree Bank (PTB) dataset and the models selected were recurrent networks. The goal was then to correctly find a recurrent cell that can predict the next word given an incomplete sentence, and the reported metric is the perplexity.

NAS Comparison in a Standard Search Space

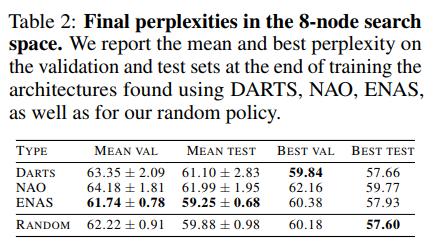

The authors first tested in a search space of 8 nodes and 4 possible operations (more info on how nodes and the search space are defined in Appendix A). For each of the search policies, 10 different seeds were used, and the models were trained for 1000 epochs.

Observations

- Random sampling is robust and consistently competitive

- The ENAS policy sampler has the lowest variance among the three tested ones. This shows that ENAS is more robust to the variance caused by the random seed of the search phase. Such a comparison of search policies would not have been possible without the authors’ framework.

NAS Comparison in a Reduced Search Space

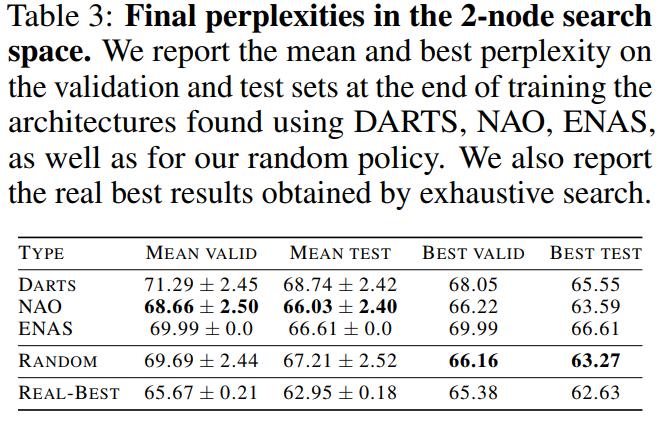

This time the authors reduced the search space to two nodes and 4 operations

Observations

- All the policies failed to find the architecture that actually performs best

- The best architecture sampled by any search policy was found by the random search, as in the 8-node case.

- Even in a space this small, on average, the random policy still yields comparable results to the other search strategies

- The ENAS policy always converged to the same architecture

Impact of Weight Sharing

The authors then tried to see the impact of weight sharing:

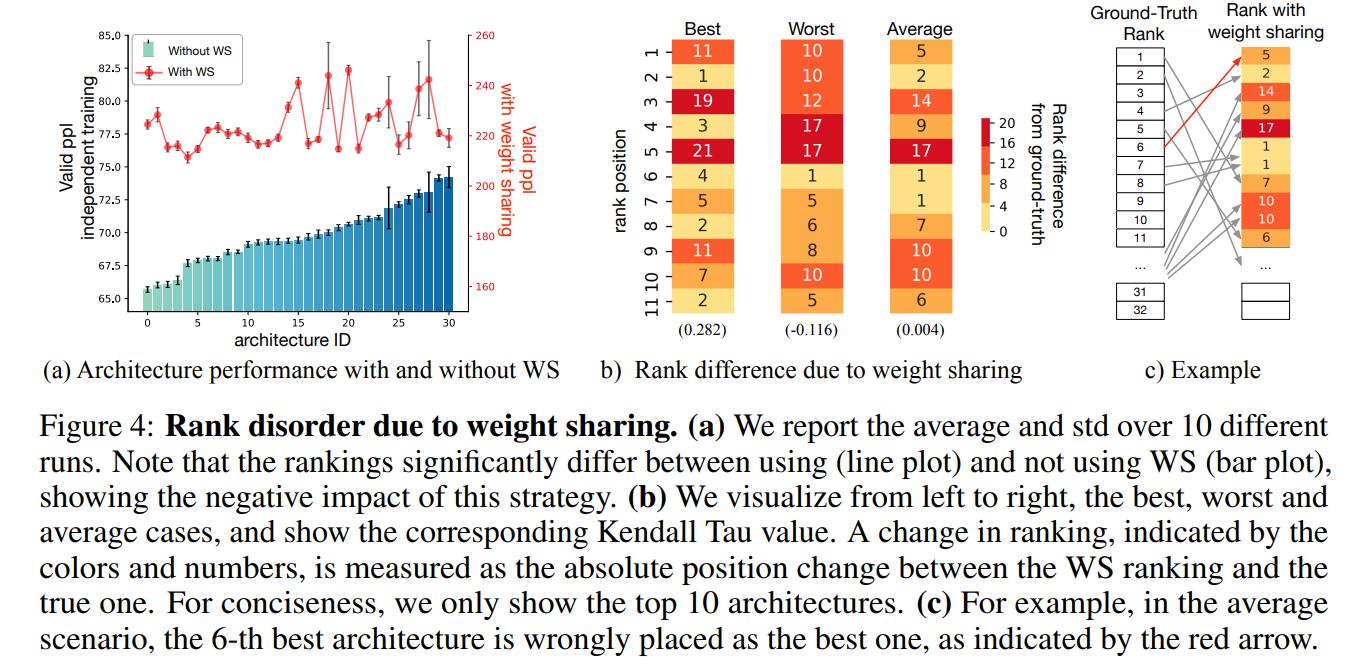

We see two potential reasons to explain the failure of NAS algorithms: 1) All models in the reduced search space perform similarly, thus finding any of them is a success; and 2) Weight sharing reduces the correlation between the ranking in the search phase and the ranking of the evaluation phase

Observations

- The difference in architecture performance is not related to the use of different random seeds, as indicated by the error bars in Figure 4(a).

- The behavior of the WS rankings is greatly affected by the changing of the seed.

- For all of the 10 runs, the Kendall Tau metrics are close to zero, which suggests a lack of correlation between the WS rankings and the true one.

Conclusions

We have observed that, surprisingly, the search policies of state-of-the-art NAS techniques are no better than random, and have traced the reason for this to the use of (i) a constrained search space and (ii) weight sharing, which shuffles the architecture ranking during the search, thus negatively impacting it.