A Few Useful Things to Know about Machine Learning

Notice

This paper/review was written before deep learning methods made into the stage to dominate virtually any image analysis/computer vision problem, or any another problem involving some prediction. So some of its statements may require some reformatting in the deep learning context.

In any case, it may well deserve a read.

Summary

Developing successful machine learning (ML) applications requires some experience that is hard to find in textbooks. This article summarizes twelve key lessons that machine learning researchers and practitioners have learned. These include pitfalls to avoid, important issues to focus on, and answers to common questions.

The paper focuses on aspects of ML applied to classification tasks.

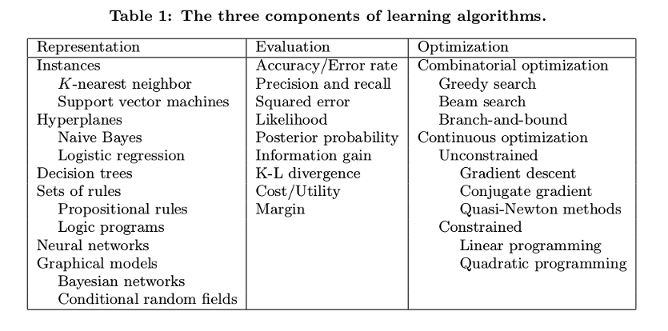

- LEARNING = REPRESENTATION + EVALUATION + OPTIMIZATION

Basic components of a ML task

- Representation: A classifier must be represented in some formal language that the computer can handle. A related question is how to represent the input, i.e., what features to use.

- Evaluation: An evaluation function (also called objective function or scoring function) is needed to distinguish good classifiers from bad ones.

- Optimization: A method to maximize the score/minimize the loss.

- IT’S GENERALIZATION THAT COUNTS

The fundamental goal of machine learning is to generalize beyond the examples in the training set. This is because, no matter how much data we have, it is very unlikely that we will see those exact examples again at test time.

The algorithm must perform well in unseen data; having a good training accuracy may mean that the method has just memorized the examples it has seen.

So keep testing data aside for the final evaluation.

- DATA ALONE IS NOT ENOUGH

Generalization being the goal has another major consequence: data alone is not enough, no matter how much of it you have. Learners combine knowledge with data to grow programs.

- OVERFITTING HAS MANY FACES

If the knowledge and data we have are not sufficient to completely determine the correct classifier we run the risk of just hallucinating a classifier (or parts of it) that is not grounded in reality, and is simply encoding random quirks in the data.

Overfitting comes in many forms that are not immediately obvious. One way to understand overfitting is by decomposing generalization error into bias and variance. Bias is a learner’s tendency to consistently learn the same wrong thing. Variance is the tendency to learn random things irrespective of the real signal.

- Strong false assumptions can be better than weak true ones, because a learner with the latter needs more data to avoid overfitting.

- Regularization functions added to the evaluation function help ensuring that the method explains the data with the simplest possible model.

- Cross-validation can help to mitigate overfitting.

- A common misconception about overfitting is that it is caused by noise.

- Control the fraction of falsely accepted non-null hypotheses, known as the false discovery rate.

- INTUITION FAILS IN HIGH DIMENSIONS

The curse of dimensionality refers to either the fact that methods that work fine in low dimensions become intractable when the input is high-dimensional, or to the fact that Generalizing correctly becomes exponentially harder aseta the dimensionality (number of features) of the examples grows.

Our intuitions, which come from a threedimensional world, often do not apply in high-dimensional ones.

- THEORETICAL GUARANTEES ARE NOT WHAT THEY SEEM

Machine learning papers are full of theoretical guarantees. Even though in principle more data means that more complex classifiers can be learned, in practice simpler classifiers end up being used, because complex ones take too long to learn. Part of the answer is to come up with fast ways to learn complex classifiers.

The main role of theoretical guarantees in machine learning is not as a criterion for practical decisions, but as a source of understanding and driving force for algorithm design.

Just because a learner has a theoretical justification and works in practice does not mean the former is the reason for the latter.

- FEATURE ENGINEERING IS (WAS) THE KEY

At the end of the day, some machine learning projects succeed and some fail. What makes the difference? Easily the most important factor is the features used. Often, the raw data is not in a form that is amenable to learning, but you can construct features from it that are.

Machine learning is not a one-shot process of building a data set and running a learner, but rather an iterative process of running the learner, analyzing the results, modifying the data and/or the learner, and repeating.

Features that look irrelevant in isolation may be relevant in combination.

Although the claims in this section may hold to a certain extent for some types of images, feature engineering is becoming less important with deep learning. For example, with RGB images, engineered features are not used anymore.

- MORE DATA BEATS A CLEVERER ALGORITHM

Pragmatically the quickest path to success is often to just get more data. As a rule of thumb, a dumb algorithm with lots and lots of data beats a clever one with modest amounts of it.

Enormous mountains of data are available, but there is not enough time to process it, so it goes unused. In the end, the biggest bottleneck is not data or CPU cycles, but human cycles.

Similarly, even though in principle more data means that more complex classifiers can be learned, in practice simpler classifiers end up being used, because complex ones take too long to learn. Part of the answer is to come up with fast ways to learn complex classifiers.

In summary:

- If you can incorporate more data, do it (instead of changing your classifier).

- If you have very few samples, and you cannot get much more (e.g. medical imaging), you should put more effort on encoding priors into your classifier.

- LEARN MANY MODELS, NOT JUST ONE

The best learner varies from application to application. If instead of selecting the best variation found, we combine many variations, the results are better -often much better-. Although the downside of model ensembling is requiring a \(n\)-fold training time, little extra effort is required for the user.

Ensembling deep models typically yields an improvement of a few percentual points. It is mostly useful for challenges. but at the cost of \(n\)-times the training and prediction time.

Model ensembles examples: bagging, boosting,etc.

- SIMPLICITY DOES NOT IMPLY ACCURACY

Occam’s razor: entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity. In machine learning, this is often taken to mean that, given two classifiers with the same training error, the simpler of the two will likely have the lowest test error.

But counter-examples exist: there is no necessary connection between the number of parameters of a model and its tendency to overfit (e.g. SVMs).

The conclusion is that simpler hypotheses should be preferred because simplicity is a virtue in its own right, not because of a hypothetical connection with accuracy.

- REPRESENTABLE DOES NOT IMPLY LEARNABLE

Just because a function can be represented does not mean it can be learned. It pays to try different learners (and possibly combine them). Given finite data, time and memory, standard learners can learn only a tiny subset of all possible functions, and these subsets are different for learners with different representations.

Finding methods to learn deeper representations is one of the major research frontiers in machine learning.

- CORRELATION DOES NOT IMPLY CAUSATION

More often than not, the goal of learning predictive models is to use them as guides to action. But short of actually doing the experiment it is difficult to tell. Machine learning is usually applied to observational data, where the predictive variables are not under the control of the learner, as opposed to experimental data, where they are.

Final remarks

The book The Master Algorithm: How the Quest for the Ultimate Learning Machine Will Remake Our World by the same author may provide further insight into the subject.