Gradients explode - Deep Networks are shallow - ResNet explained

In this awkwardly-organized paper with 17 pages of main content and 38 pages of appendix, the authors tackle many research directions related to gradient explosion/vanishing and the training of deep networks. They introduce many theoretic contributions, backed by experiments on 50-layer MLP’s of width 100.

Gradient explosion

One of their main contributions is the Gradient Scale Coefficient (GSC), a measure of the extent at which gradients explode (or vanish) in a network. They argue that other notions are insufficient at measuring - or even describing - the phenomena of gradient explosion. They also argue that gradient explosion is important, as it prevents deep networks from being successfully trained.

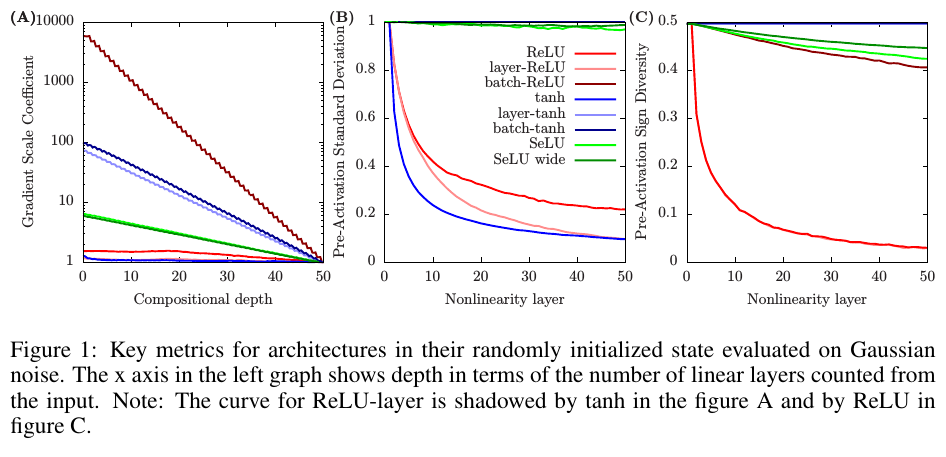

In figure 1A below, we see that many architectures have a linear progression of the GSC (in log-space), which denotes gradient explosion. Fig 1B and 1C are explained later.

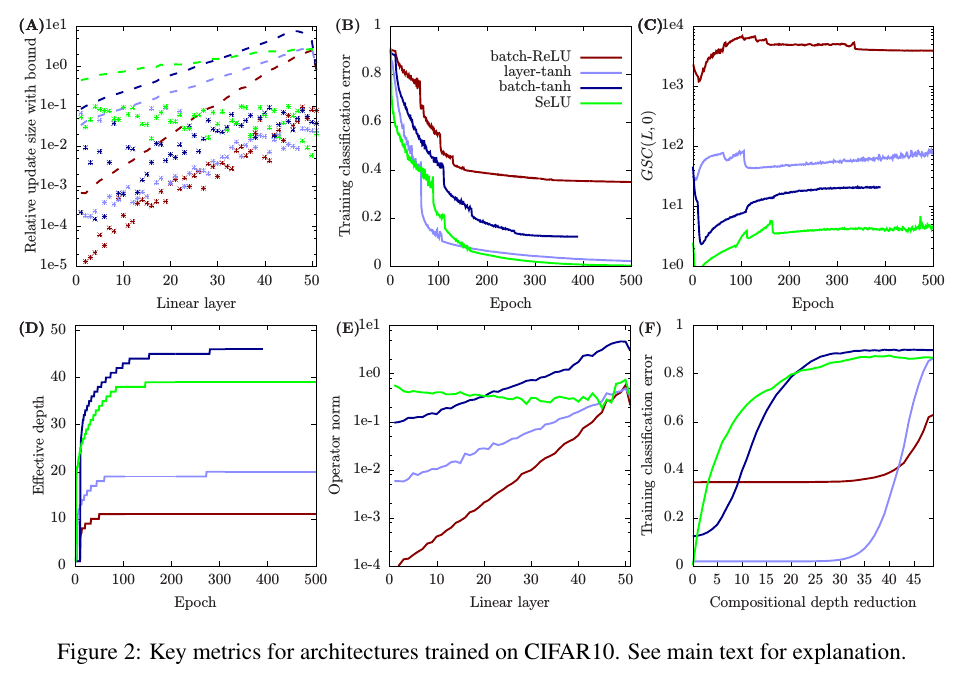

Another contribution is a method for computing the effective depth of a network. The authors explain that the effective depth is (almost) always lesser than the compositional depth (they define the compositional depth as the number of parametrized layers) of a network. This can be caused by gradient explosion. To check their estimation of effective depth, they do the following experiment. They progressively replace the last layers of a network with a single layer, which is a Taylor expansion of the replaced layers.

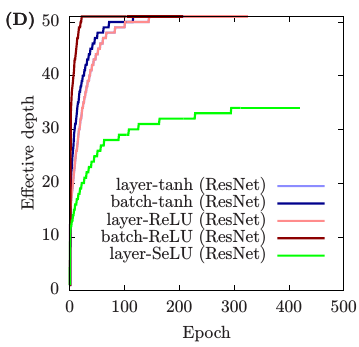

In the figure below, (D) is the progression of effective depth with training epochs; (F) is the effect of the experiments with the Taylor expansion on the training error. As you can see, an architecture with a greater effective depth will suffer sooner from a compositional depth reduction. Observe the other subplots at your own risk.

Collapsing domain

The collapsing domain problem is another cause for a small effective depth. When the pre-activations that are fed into a nonlinearity are highly similar, the nonlinearity can be well-approximated by a linear function. In these cases, we call the layer pseudo-linear. For example, a tanh network that is pseudo-linear beyond compositional depth \(k\) has approximately the representational capacity of a depth \(k + 1\) network. The author propose two ways of measuring this problem:

- Pre-activation standard deviation

- Pre-activation sign diversity, defined as \(\frac{min(P, N)}{P+N}\), where \(P\) is the number of positive neurons and \(N\) the number of negative neurons. This measure is particularly important for ReLU networks, where nonlinearities with low sign diversity can be well approximated by either the identity function or the zero function.

You have now unlocked the figure 1B and 1C! Hurray!!!

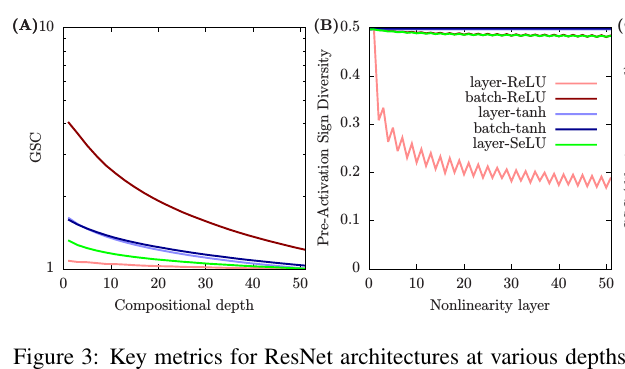

ResNet naturally reduces gradient explosion

The authors demonstrate that ResNets have lower GSC, and they argue that these architectures are mathematically simpler than vanilla networks. They explain that residual connections introduce what they call dilution, which prevents some of the gradient explosion, and help attain a higher effective depth.

Practical recommendations

The authors list many practical recommendations and implications for deep learning research. Here are a few recommendations:

- Train the network from an orthogonal initial state. Initialize the network such that it is a series of orthogonal linear transformations. See appendix H for a method to achieve such an initial state. ResNet’s initial state is naturally approximately orthogonal.

- Use residual connections. Residual connections reduce gradient explosion and domain collapse. Normalization layers, careful initialization, SeLU, etc. can prevent gradient explosion. Adam and RMSprop can improve performance but do not reduce the pathologies.

- Add width instead of depth. More depth exacerbates pathologies and can lead to low effective depth. If there is a fixed parameter budget, it may be better spent on width than extreme depth.